In discography—the “bibliography” of recorded sound—inferences based on patterns have traditionally been discouraged. If matrices 6146-6148 and 6150-6154 are all known to have been recorded by a particular musician on 17 April 1923, for instance, the experts would caution us against assuming the same of matrix 6149. And they’d be quite right: the recordings could have been shuffled out of numerical order due to entropic factors beyond our ken. From this standpoint, apparent patterns can be deceptive; they prove nothing. Serious discographers, the implication runs, shouldn’t waste their time on such stuff.

But there are cases in which I believe searching out patterns in discographic data can shed light on recordings and on the recording programs that produced them. In this blog post, I’d like to present three examples of a distinctive but easy-to-miss pattern I find particularly suggestive—one in which it seems that a sequence of numbers was first assigned to selections in chronological order, some of the selections were later deleted, and the resulting gaps were then filled in with new selections. The examples I’ll be discussing are:

- The two oldest known commercial record catalogs, issued by the North American Phonograph Company and New York Phonograph Company in 1890.

- The early A-series of seven-inch gramophone discs released in 1900 by the concern that later became the Victor Talking Machine Company.

- The “Climax Records” manufactured by the Globe Record Company in 1901-1902 and the first “Columbia Disc Records” manufactured by the Columbia Phonograph Company starting in 1902.

I.

Plenty of sources will tell you that the first-ever record catalog was put out by the Columbia Phonograph Company, but as with many such claims made about Columbia’s alleged innovations in the record business, this is a load of bunk. The world’s first record catalog was actually published by the North American Phonograph Company, the parent company that controlled the marketing of Edison’s phonograph throughout the United States. This catalog was issued “a few days” before January 17, 1890, when it was mentioned in a circular sent out by North American to all the local sub-companies (including Columbia) that controlled local phonograph rentals and sale of supplies. It’s an exceptionally rare piece of ephemera: Thomas Edison National Historical Park has a photocopy, viewable online here, but their original print copy was stolen, and I’m not aware of any other extant specimens. Its listings were organized into sections based on genre—”brass band,” “parlor orchestra,” “cornet,” and so forth—with individual selections numbered starting over at one in each section, such that orders would have needed to specify both a genre and a number: Cornet #4, for example. The list of selections was based in turn on an inventory which had been furnished to North American by the Edison Laboratory back in December with a promise from Edison’s secretary, Alfred Ord Tate: “We will see that a number of the selections catalogued are always kept on hand, from which to fill orders.”

That was a big change. Since May 1889, North American had been offering “musical phonograms, in boxes of 6 and 12 (assorted),” but there had been no provision for customers to choose anything more specific than that. At the time, no acceptable method had yet been found of duplicating commercially viable musical records on phonograph cylinders. Instead, all of the recordings North American was selling were “originals” cut at the Edison Laboratory with multiple phonographs clustered around the performer(s) in a semicircle, all running at once. Once the resulting cylinders were gone, they were gone. Production was accordingly unpredictable, and the offer of “assorted” phonograms had given the operation some much-needed flexibility: laboratory staff had been able to throw together an assortment of whatever happened to be available in stock, depending on who had come in to make recordings lately, what they had opted to play, and how successful the results had been (only a certain percentage passed quality control with the requisite grade of “A”). Not everyone had been satisfied with that arrangement, though, judging from the following letter (from W. C. Smith, New Jersey Phonograph Company, to Alfred Ord Tate, 28 June 1889, ENHS correspondence box 1889:22, folder D-89-63):

A customer of ours who visited you with one of our Employees some time since and who has paid us for 12 of your musical cylinders which he proposes to use in giving Exhibitions returned home with the understanding that you would send him a catalogue from which he could make his selection. He has his machine, is ready to go out but not hearing from either you or us is becoming restive.

On that occasion, the Edison Laboratory had merely pulled together a list of current inventory for the customer to choose from, without committing to anything further. However, pressure for a real catalog had continued to mount, culminating in the publication in January 1890 of the Catalogue of Musical Phonograms for the Phonograph, with its statement: “The following list of Musical Phonograms we propose to keep in stock.” Orders keyed to this catalog must have begun coming in to North American during the last two weeks of the month and would have been forwarded to the Edison Phonograph Works, which would have sent them in turn to the Edison Laboratory to be filled.

It’s hard to know exactly what was going on behind the scenes, but I’m pretty sure this was a case of upper administration making unwise commitments based on a poor understanding of on-the-ground reality. “We will see that a number of the selections catalogued are always kept on hand, from which to fill orders,” Tate had assured North American; but Walter Miller, who was actually in charge of the recording program at the time, likely panicked when he found out about this promise. Furnishing “assorted” phonograms had been challenging enough, but now he was suddenly being called upon to supply specific selections on request, and in any desired quantity. I suspect he must have objected that this just wasn’t feasible without a thorough restructuring of the recording program which there was no time to undertake.

On January 25, 1890—just as the first orders based on the new catalog would have been reaching the Edison Laboratory—the following letter went out above Edison’s signature to the Edison Phonograph Works:

I have read the correspondence from various Phonograph Companies, addressed to the North American Phonograph Co., and referred by them to yourselves complaining of the quality of musical records furnished from my Laboratory.

In response to your inquiries regarding these complaints I beg to say that I have permitted musical records to be made here purely as a matter of accommodation to the North American people. The work has taken up a considerable portion of space which I could have occupied to much better advantage; and I allowed it to go on simply to oblige those who had no facilities for making these records themselves. This necessitated not a little organization as we have been producing from one hundred to two hundred cylinders per day, each one of which had to pass through the hands of an employé whose sole duty it was to select only those which were absolutely perfect, the others being discarded and turned off. Those reserved for marketing were furnished you at cost price.

So long as the work required none of my personal attention I had no objection to its being carried on in my Laboratory, but the number of complaints that I have been asked to read lately has shown me very clearly that this business must be handled by some one who has more time to devote to it than I have; or perhaps it might be more satisfactory for the different phonograph companies to make their own musical records.

I have today closed my Music Room and discharged the staff lately employed there. If you desire any information as to our methods; dimensions of funnels or any particulars regarding details I will be very happy to furnish them to you.

The stock of records which we have on hand here will be sent to your storeroom on Monday.

Nothing was said here about the constraints imposed by the newly-published catalog, but the timing suggests that this might have been the real reason for shutting down the making of records at the Edison Laboratory—a reason that couldn’t have been admitted without some embarrassment, of course, since it would have involved a formal commitment which the laboratory had made but wasn’t able to fulfill. Thomas Lombard, Vice President of the North American Phonograph Company, gave his perspective on the development a couple years later at the third annual convention of the National Phonograph Association (see page C83 here):

When Mr. Edison first made musical records, as you all remember, the character of the records was very fine and all that sort of thing, but unfortunately they were not up to the mark in their shipping department, and as a consequence we used to get all kinds of complaints as to how records were received. It resulted after a considerable time in Mr. Edison getting tired of those complaints and he said to the North American Company, “You had better make them yourself for a time until we get a little further along and improve the method of making them and shipping them.” That was rather a sudden determination on Mr. Edison’s part and I was put in a hole with about 600 orders for records to fill. I immediately started in to see how we could fill those orders and made some arrangement with the New York Company to do so.

The New York Phonograph Company was a local sub-company situated conveniently near the national headquarters of the North American Phonograph Company in New York City, and it had also been making musical records of its own for some time, exploiting the large talent pool available to it in the metropolis. About this time, it put out a record catalog of its own, a copy of which is preserved at Thomas Edison National Historical Park (Primary Printed Series, Box 28, “New York Phonograph Company” folder).

This catalog uses much the same fonts, layout, and numbering system as the earlier North American catalog, and some of the genre-based sections are identical as well. For example, the cornet and clarionet sections are all precisely the same. This would have been convenient, of course, if North American had turned to the New York company to fill the orders for six hundred cylinders it had reportedly received from around the country based on the earlier catalog, as Lombard recalled.

This catalog uses much the same fonts, layout, and numbering system as the earlier North American catalog, and some of the genre-based sections are identical as well. For example, the cornet and clarionet sections are all precisely the same. This would have been convenient, of course, if North American had turned to the New York company to fill the orders for six hundred cylinders it had reportedly received from around the country based on the earlier catalog, as Lombard recalled.

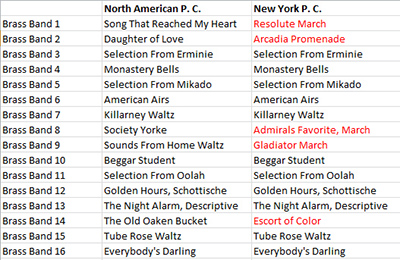

However, some other sections had undergone interesting changes. Here’s a side-by-side comparison of the sections labeled “parlor orchestra” in the North American catalog and “orchestra” in the New York catalog:

The New York company had added “Gypsy, Mazurka” to its list of offerings, tacked onto the end of the earlier fifteen-item sequence as number sixteen. However, it had also replaced the former selection number thirteen, “Columbus,” with a new selection number thirteen: “Perpetual Motion, Galop.” Five similar substitutions may be seen in the “brass band” section:

The New York company had added “Gypsy, Mazurka” to its list of offerings, tacked onto the end of the earlier fifteen-item sequence as number sixteen. However, it had also replaced the former selection number thirteen, “Columbus,” with a new selection number thirteen: “Perpetual Motion, Galop.” Five similar substitutions may be seen in the “brass band” section:

It’s easy to infer what must have happened. The Edison Laboratory and New York Phonograph Company drew on different performers in their record-making work. Walter Miller’s operation at the Edison Laboratory had relied on Issler’s Orchestra and Duffy and Imgrund’s Fifth Regiment Band, for instance, but judging from selection-and-performer combinations listed in “The Edison Phonograph,” Atlanta Constitution, July 23, 1890, p. 7, the New York Phonograph Company relied instead on Dodsworth’s Orchestra and Cappa’s Seventh New York Regiment Band. Issler’s Orchestra and Dodsworth’s Orchestra presumably didn’t share identical repertoires, nor did Duffy and Imgrund’s Fifth Regiment Band and Cappa’s Seventh New York Regiment Band, so there must have been a few selections in the earlier catalog which the New York company’s performers didn’t know how to play. Simply leaving them out would have created gaps in the numbering, with the sequence running 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16 for brass band selections. Depending on how inventory was stored—perhaps in numbered shelving compartments—this approach might also have resulted in confusion or wastage of space. Based on these or other considerations, the New York company had instead filled in the gaps in the sequence with new selections, providing a rare scrap of insight into the strategies pursued by the nascent recording industry as it struggled to come up with consistent product lines. It’s unclear to me whether anyone who had ordered brass band #1 from the North American catalog (“Song That Reached My Heart”) might have run the risk of getting brass band #1 from the New York catalog instead (“Resolute March”), or whether they’d have been likely to complain. Personally, I’d be happy to have a copy of either one today.

It’s easy to infer what must have happened. The Edison Laboratory and New York Phonograph Company drew on different performers in their record-making work. Walter Miller’s operation at the Edison Laboratory had relied on Issler’s Orchestra and Duffy and Imgrund’s Fifth Regiment Band, for instance, but judging from selection-and-performer combinations listed in “The Edison Phonograph,” Atlanta Constitution, July 23, 1890, p. 7, the New York Phonograph Company relied instead on Dodsworth’s Orchestra and Cappa’s Seventh New York Regiment Band. Issler’s Orchestra and Dodsworth’s Orchestra presumably didn’t share identical repertoires, nor did Duffy and Imgrund’s Fifth Regiment Band and Cappa’s Seventh New York Regiment Band, so there must have been a few selections in the earlier catalog which the New York company’s performers didn’t know how to play. Simply leaving them out would have created gaps in the numbering, with the sequence running 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16 for brass band selections. Depending on how inventory was stored—perhaps in numbered shelving compartments—this approach might also have resulted in confusion or wastage of space. Based on these or other considerations, the New York company had instead filled in the gaps in the sequence with new selections, providing a rare scrap of insight into the strategies pursued by the nascent recording industry as it struggled to come up with consistent product lines. It’s unclear to me whether anyone who had ordered brass band #1 from the North American catalog (“Song That Reached My Heart”) might have run the risk of getting brass band #1 from the New York catalog instead (“Resolute March”), or whether they’d have been likely to complain. Personally, I’d be happy to have a copy of either one today.

II.

The corporate successors of the Victor Talking Machine Company may have bulldozed most of its early master recordings into the Delaware River in the 1960s after demolishing the building in which they had been preserved up until that point, but they’ve at least done a good job of retaining ledgers that document the dates on which those recordings had been made. In fact, the information in these ledgers dates all the way back to recording sessions that took place in mid-1900, before the adoption of the “Victor” name. This was the period when Eldridge R. Johnson first began seriously implementing his own process for mastering gramophone discs in wax; at first, he planned to channel the results through the Berliner Gramophone Company, but instead he ended up establishing his own company in an effort to insulate himself from some legal entanglements in which Berliner had become embroiled with sales agent Frank Seaman. I’ll refer to Johnson’s operation here as “Victor” for the sake of convenience, but its earliest commercially released discs—the ones I’ll be describing here—initially bore paper labels identifying them as “Improved Gram-o-phone Records” manufactured by the “Consolidated Talking Machine Company” of Philadelphia. A couple examples from my own collection are shown below—not the cleanest examples, but they’re what I’ve got. Note that the word “Improved” has been intentionally scratched out on the second label; apparently someone didn’t think it was much of an improvement!

I once had the opportunity to look briefly at facsimiles of a few early Victor ledger pages, and from what I could tell at a glance, it looked as though data about the very first recording sessions had been copied over out of chronological order from some earlier (perhaps lost) source. Thus, we can’t rule out the possibility of errors creeping in at that point through the misreading of unclear handwriting or formatting. The early data from these ledgers formed the basis of two print volumes of The Encyclopedic Discography of Victor Recordings by Ted Fagan and William R. Moran, and it was incorporated more recently into an online database since absorbed into the broader Discography of American Historical Recordings.

I once had the opportunity to look briefly at facsimiles of a few early Victor ledger pages, and from what I could tell at a glance, it looked as though data about the very first recording sessions had been copied over out of chronological order from some earlier (perhaps lost) source. Thus, we can’t rule out the possibility of errors creeping in at that point through the misreading of unclear handwriting or formatting. The early data from these ledgers formed the basis of two print volumes of The Encyclopedic Discography of Victor Recordings by Ted Fagan and William R. Moran, and it was incorporated more recently into an online database since absorbed into the broader Discography of American Historical Recordings.

The first Victor discs bore catalog numbers in an A-series, and these same numbers were used to track matrices in the ledgers—a situation that persisted until matrix numbers separate from catalog numbers were instituted in 1903 (the earlier matrices are often called “pre-matrix”). Printed disc labels stated simply “A-1,” “A-2,” and so forth (and later dropped the “A”), but other numbers often appear in the shellac at nine o’clock to distinguish different “takes”—that is, discrete recordings of the same selection that could be substituted for each other in production. Victor’s standard practice was to leave the first take unnumbered, so the absence of a take number typically means “take 1.” A complete Victor matrix identifier includes a take number, formatted like this: A-1-1 (for take one), A-1-2 (for take two), and so on. Higher-numbered takes were often recorded on later dates.

At first glance, the logic behind the initial sequence of numbers in the Victor A-series is elusive. Original recording dates and content are all jumbled together out of order: for example, A-2-1 (“Colored Preacher” by George Graham) is dated 14 May 1900, well before A-1-1 (“Departure” by George Broderick), which is dated 28 June 1900. Allen Koenigsberg (Patent History of the Phonograph, 56) suggests that the numbers reflect the order of release rather than the order of recording, but in fact the first few hundred titles were all “released” simultaneously in the company’s first known catalog. Tim Gracyk (“Eldridge R. Johnson’s First Numbered Record,” Victrola and 78 Journal 10 (Winter 1996), 36) supposes that there must have been “a random process of assigning takes with release numbers, with that process being unknown today.” When I see the word “random,” though, I can’t help but wonder whether there’s a pattern lurking there waiting to be discovered.

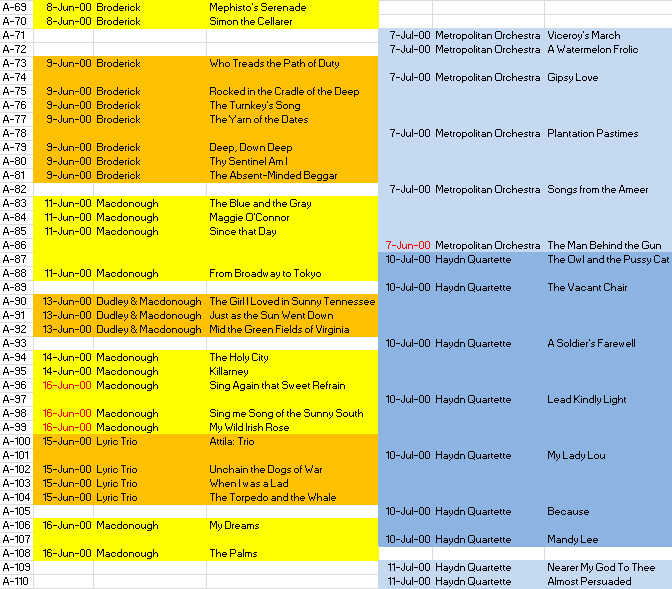

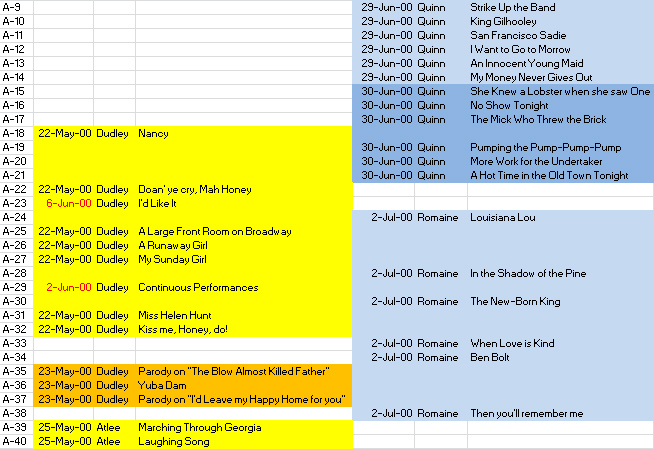

So let’s hypothesize that something had happened here much like what we saw earlier with the North American and New York Phonograph Company catalogs: that the number A-1 had first been assigned to some other selection that had later been deleted, and that “Departure” by Broderick had been assigned to fill the resulting gap on or after 28 June 1900, as the first in a sequence of similar substitutions. To test that hypothesis, let’s divide all selections into two categories—those with a first take dated before 28 June 1900, and those with a first take dated on or after 28 June 1900—and see what patterns emerge. Here’s the sequence running from A-69 through A-110, with earlier sections shown in the left column and later sections shown in the right column:

The two columns divide neatly into blocks of selections first secured from particular performers during particular recording sessions in approximate chronological order—just as we’d expect if my hypothesis is correct. Thus, A-101 was likely assigned first to an undocumented selection by the Lyric Trio dated 15 June 1900 as one of five or six selections secured from them during the same session (A-100 through A-104 or A-105); but that selection was probably later rejected and deleted, with the gap being filled with “My Lady Lou” by the Haydn Quartette as one of seven selections secured from them on 10 July 1900 (inserted in whatever openings in the sequence were then available starting at A-87).

The two columns divide neatly into blocks of selections first secured from particular performers during particular recording sessions in approximate chronological order—just as we’d expect if my hypothesis is correct. Thus, A-101 was likely assigned first to an undocumented selection by the Lyric Trio dated 15 June 1900 as one of five or six selections secured from them during the same session (A-100 through A-104 or A-105); but that selection was probably later rejected and deleted, with the gap being filled with “My Lady Lou” by the Haydn Quartette as one of seven selections secured from them on 10 July 1900 (inserted in whatever openings in the sequence were then available starting at A-87).

However, there are two anomalies here worth examining. First, A-86 was allegedly dated 7 June 1900, but since it falls at the end of a block of recordings by the same orchestra all dated 7 July 1900, I strongly suspect that the June date is due to a copying error, and I’ve accordingly placed the selection into the right column rather than the left column. And then there are A-96, A-98, and A-99, all with first takes dated 16 June, followed by a block of selections by the Lyric Trio with takes dated 15 June, seemingly out of order (if only by a single day). Perhaps selections A-94 through A-99 had already been assigned to selections by Harry Macdonough on 14 June, but no successful takes had yet been secured of them, and the first takes to pass some important quality control step were instead created a couple days later, on 16 June. If we look at another part of the sequence running from A-9 through A-40, I believe we can see something similar happening with a couple selections by S. H. Dudley:

The larger-scale division of Dudley’s selections into groups based on whether the first takes are dated 22 May (A-18 through A-32) or 23 May (A-35 through A-37) suggests that numbers were originally assigned to selections in strict chronological order. In this scenario, A-23 and A-29 might already have been assigned to selections on 22 May, but with no usable takes secured until subsequent recording sessions in June. One early double-faced pressing has been reported of “Nancy” and “I’d Like It” with handwritten inscriptions in the shellac itself: titles on both sides, plus a note on one side—we don’t know which one—reading “Good—Johnson” (see Tim Brooks, “Seeing Double! The First Two-Sided Records.” Antique Phonograph Monthly 3:6 (1975): 1, 3-4, 6-7, 16). The two sides aren’t numbered in any way, either as to catalog number or take. However, my bet is that “Nancy” is the side marked “good,” and that it corresponds to A-18-1, dated 22 May 1900, whereas “I’d Like It” was a rejected take of A-23 recorded on the same day and never received a take number, leaving take 1 free to be assigned on 6 June 1900 instead.

The larger-scale division of Dudley’s selections into groups based on whether the first takes are dated 22 May (A-18 through A-32) or 23 May (A-35 through A-37) suggests that numbers were originally assigned to selections in strict chronological order. In this scenario, A-23 and A-29 might already have been assigned to selections on 22 May, but with no usable takes secured until subsequent recording sessions in June. One early double-faced pressing has been reported of “Nancy” and “I’d Like It” with handwritten inscriptions in the shellac itself: titles on both sides, plus a note on one side—we don’t know which one—reading “Good—Johnson” (see Tim Brooks, “Seeing Double! The First Two-Sided Records.” Antique Phonograph Monthly 3:6 (1975): 1, 3-4, 6-7, 16). The two sides aren’t numbered in any way, either as to catalog number or take. However, my bet is that “Nancy” is the side marked “good,” and that it corresponds to A-18-1, dated 22 May 1900, whereas “I’d Like It” was a rejected take of A-23 recorded on the same day and never received a take number, leaving take 1 free to be assigned on 6 June 1900 instead.

There are also a few ultra-rare pressings of A-series discs that have typeset title, artist, and catalog number information in the shellac along with the statement: “This Record is Licensed For Use Only On The Berliner Gramophone” (double-faced examples are described and illustrated in Brooks, “Seeing Double!,” op. cit.; single-faced examples in Sherman, Collector’s Guide to Victor Records, 2nd edition, p. 30). One such pressing of A-72, “War is a Bountiful Jade” by George Broderick is marked “destroy.” That selection isn’t found in the ledgers, but A-72 falls squarely in the middle of a bunch of other Broderick selections dated 8-9 June 1900, right where we’d expect there to have been a deletion. Another pressing marked as “licensed for use only on the Berliner Gramophone” couples two takes of A-111, both dated 11 July 1900 in the ledgers, so this distinctive layout must have been current at or after that time. Each of the test pressings I’ve mentioned so far except for the rejected A-72 reportedly also has a spoken announcement that identifies it as a “Berliner Gramophone Record” or as made “for the Berliner Gramophone Company.” Apparently the deletions (e.g., of A-72) and the substitutions (e.g., of A-111) both took place during the time when Johnson was having stampers marked and announced as Berliner gramophone products.

There are also a few ultra-rare pressings of A-series discs that have typeset title, artist, and catalog number information in the shellac along with the statement: “This Record is Licensed For Use Only On The Berliner Gramophone” (double-faced examples are described and illustrated in Brooks, “Seeing Double!,” op. cit.; single-faced examples in Sherman, Collector’s Guide to Victor Records, 2nd edition, p. 30). One such pressing of A-72, “War is a Bountiful Jade” by George Broderick is marked “destroy.” That selection isn’t found in the ledgers, but A-72 falls squarely in the middle of a bunch of other Broderick selections dated 8-9 June 1900, right where we’d expect there to have been a deletion. Another pressing marked as “licensed for use only on the Berliner Gramophone” couples two takes of A-111, both dated 11 July 1900 in the ledgers, so this distinctive layout must have been current at or after that time. Each of the test pressings I’ve mentioned so far except for the rejected A-72 reportedly also has a spoken announcement that identifies it as a “Berliner Gramophone Record” or as made “for the Berliner Gramophone Company.” Apparently the deletions (e.g., of A-72) and the substitutions (e.g., of A-111) both took place during the time when Johnson was having stampers marked and announced as Berliner gramophone products.

A memoir by Johnson employee Harry O. Sooy provides some intriguing context for all this:

Well, then came the hustle of getting as quickly as possible a variety of records, or master matrices, together with a commercial value, to establish a record catalog of E. R. Johnson’s records, which proved to be quite a problem, as most all of our previous records that we had been recording (except those marked “Experimental”) whether vocal or instrumental, contained the announcement recorded in the record “Berliner Gramophone Company,” which, of course, we could not use. So, the only way we were to produce a record catalog for Mr. Johnson was to use many matrices which were made as experimental records, and had the word “Experimental” engraved in their face. We also knew we could not let pressings go out to the public with the word “Experimental” engraved in their face, so I, being the apprentice in the department, was elected to erase the word “Experimental” from the copper matrices. After some long days, running well up into the evening, I had a goodly supply of Experimental Matrices ready to make pressings from for the Eldridge R. Johnson catalog. These Experimental Matrices, together with the list of selections being recorded daily up to the time of the first announcement of Johnson Records, made up the small variety of selections for the first E. R. Johnson Record Catalog.

That’s how Sooy remembered things unfolding many years later. His memory may have been faulty when it came to details, but there’s surely some kernel of truth to the overall picture he paints. One problem had supposedly been the prevalence of Berliner-specific announcements, something on which Sooy had elaborated earlier in his memoir:

During my apprenticeship at recording Mr. Johnson told me that when I had learned the business in all probability I would be transferred, with the process, to the Berliner Gramophone Co., as he was contemplating selling it to them at some future time. We made Band, Banjo, Recitation and Vocal records, etc., supposedly for the Berliner Gramophone Co., each record having the following announcement recorded in it—“Berliner Gramophone Record.” Mr. Child, who was at that time employed by the Berliner Gramophone Co., furnished the talent and was chief announcer.

Some recordings with Berliner announcements did in fact make it into Johnson’s commercial production, perhaps by mistake, including A-186 (on YouTube, presumably take 1 or 2, recorded 26 July 1900; I appreciate the data point, but I also cringe when I see discs of such rarity being played with steel needles on vintage equipment). Also interesting is Sooy’s recollection about needing to erase visible markings from stampers. I’m skeptical about any stampers having been marked with the specific word “experimental,” but experimental matrices may well have had markings along the lines of “Good—Johnson,” which would have looked odd on a commercially manufactured product. On the other hand, I assume that any stampers marked “licensed for use only on the Berliner Gramophone” would also have needed to have these inscriptions erased for Johnson to use them in manufacturing on his own behalf—maybe Sooy had to do that as well. Indeed, it might have been the hassle and expense of needing to erase various experimental and Berliner-specific inscriptions from stampers, coupled with the need to provide substitute inscriptions on pressings made from those stampers, that prompted Johnson to implement paper labels, considering the language of his patent:

Heretofore it has been the practice to mark records of this class by engraving the necessary descriptive matter on the die from which the record is stamped or by etching the same upon the original record. This practice has been found to be quite expensive, inconvenient, and otherwise objectionable, and the records when so stamped are hardly legible on account of the color of the same, which is usually black or of a dark color and has to be held in a certain position, so that the light will properly fall upon the engraved matter before the same can be readily distinguished.

Here’s an educated guess about what had really happened (balancing patterns in the discographic data, the evidence of early pressings, and Sooy’s memoir):

- Johnson started the A-series in May 1900 as an “experimental” series which got off to a rocky start but was soon yielding good results. The test pressing of “Nancy” and “I Like It” may date from this period—that is, from a time when Johnson hadn’t yet given any thought to the appearance of finished commercial products.

- In June and July, Johnson began developing this into a projected commercial series on the assumption that it would be handled through the Berliner Gramophone Company. Neatly typeset title, artist, and catalog number information and Berliner licensing notices were added to new wax masters before electroplating. Any material that was deemed unsuitable for commercial use was pulled and destroyed, and the gaps this left in the numbering sequence were filled in with new selections starting on 28 June. Test pressings marked “This Record is Licensed For Use Only On The Berliner Gramophone” date from this period.

- In August, Johnson filed for a patent on paper labels and set about eliminating references to the Berliner gramophone from his existing stock of stampers. This would probably have involved erasing the typeset information from June and July 1900 stampers (since this had included a Berliner licensing notice) and trying to weed out matrices with Berliner announcements (with incomplete success). Conspicuously “experimental” notations would also have needed to be erased from the May 1900 stampers, which is what Sooy recalled doing in his memoir. Erasing the older markings must have been a time-consuming process and may have been responsible for the suspension of recording work during this month.

- In September, recording activities resumed in preparation for the launch of Johnson’s first catalog of “Improved Gram-o-phone Records,” with paper labels. Pressings made from these later matrices usually have handwritten title, performer, and date information visible in the shellac underneath the paper labels. Pressings made from earlier matrices don’t, and instead have raised, typeset catalog numbers, consistent with the methodical erasure of earlier markings from stampers and the punching in of new ones.

Let me repeat that this is just an educated guess; it could be wrong in part or in whole. However, it’s one explanation I can think of that accounts for all the various bits of evidence I’ve seen.

That said, the discographic patterning is admittedly not quite as neat as I’ve made it look so far. I chose the two sequences shown above (A-69 through A-110; A- 9 through A-40) as my illustrations because they conform best to my “gap-filling” hypothesis, but other parts of the early A-series are more puzzling. Starting at A-41, for example, there seem to be at least three overlapping blocks, and dates and take numbers are sometimes duplicated identically for multiple selections under the same number in ways I suspect may result from copying errors—perhaps the entries in a now-lost source ledger were formatted in such a way that it was sometimes ambiguous which takes belonged to which selections. There are also scattered out-of-sequence items and blocks elsewhere; see in particular the sequence from A-400 upward. More work would need to be done to resolve these and other anomalies, but I think it’s clear that they are anomalies; that there’s a definite pattern from which they deviate; and that the pattern means something, even if I’m not sure about the specifics.

III.

To backtrack a moment: Emile Berliner had been forced out of the gramophone field in the United States when his erstwhile sales agent, Frank Seaman, had formed an opposing alliance with the American Graphophone Company, the patent-wielding juggernaut associated with Columbia Records—at this point, strictly a cylinder line. For much of the years 1900 and 1901, American Graphophone licensed and marketed Seaman’s “Zon-o-phone” records, giving it a toehold in the disc record field. But in September 1901, American Graphophone suddenly threw its weight behind another manufacturer instead: the Globe Record Company. The incorporation of Globe had been reported in the New York Times of 20 July 1901:

Globe Record Company of New York City, to manufacture composition goods; capital, $10,000. Directors—J. D. Beekman, Andrew Barber, and O. W. Hensser, New York City.

The Globe Record Company’s discs, known as “Climax Records,” were pressed by the Burt Company of Milburn, New Jersey, a manufacturer of poker chips and billiard balls that had also been pressing Zon-o-phone discs. In fact, Globe is often described in secondary literature as a “subsidiary” of Burt, but I’m not sure that’s accurate; Victor historian B. L. Aldridge wrote that the “exact connection between Globe and Burt” was unknown. However, the reverse of Climax discs bore a semicircular notice, “PAT APP’D FOR,” and the only relevant patent then pending was the Joseph W. Jones patent for laterally recorded wax disc masters. The Globe Record Company’s basis for operation was thus presumably an agreement of some kind with Jones or his backer Albert T. Armstrong, who had lately engaged lawyer Philip Mauro to push the patent forward. But I’ve seen no evidence that American Graphophone was in any way involved in the founding of Globe, or that Globe initially assumed its products would be marketed through American Graphophone. Rather, an oral agreement was reportedly reached only a couple months later, in September 1901, “whereby the Globe Company was to make and sell and the other party [American Graphophone] to purchase commercial sound records.” The first Climax Records had been issued with raised title and manufacturer information in the shellac itself: “CLIMAX RECORD / GLOBE RECORD CO. / NEW YORK.” Only later was a gold-on-black paper label was introduced—sometimes found affixed over the raised markings—to acknowledge that Climax Records were “mf’d solely for” the Columbia Phonograph Company. Bottom line: the Climax Record ended up being marketed by American Graphophone, to be played on the latter company’s new “disc graphophone,” but the discs themselves were wholly independent of Columbia’s own well-established cylinder recording program.

Within a few months, business relations had soured enough to precipitate a schism. It’s hard to tell exactly why. When the Jones patent was finally granted on 10 December 1901, however, Mauro got it assigned directly to the American Graphophone Company, excluding Armstrong, on whose behalf he had supposedly been working—a breach of legal ethics that may have worked to Globe’s disadvantage (see Ray Wile, “The American Graphophone Company and the Columbia Phonograph Company Enter the Disc Record Business, 1897-1903,” ARSC Journal 22:2 (Fall 1991), 214). The American Graphophone Company—through Columbia—had apparently also fallen behind in payments to Globe. This led to the development which B. L. Aldridge recounted as follows:

On January 18, 1902, Mr. [Eldridge R.] Johnson and Mr. [Leon] Douglass personally bought the Globe Record Company of New York from the Burt Company of Milburn, New York, for $10,000. This did not include a claim which Globe had against the Columbia Phonograph Company and the American Graphophone Company which Burt was left free to collect in any way it could.

Even if Globe hadn’t originally been a Burt subsidiary, it might have become one through its own financial troubles; Burt would likely have been its main creditor, and if Columbia hadn’t been paying Globe, Globe wouldn’t have been able to pay Burt in turn. In any case, Johnson now took physical possession of Globe’s disc stampers, and American Graphophone suddenly found itself cut off from their source of discs for the new “disc graphophones.” After some initial bluster, the parties opened negotiations towards a compromise. In February, Johnson agreed to sell Globe to Columbia for the same amount it had paid ($10,000), but only on the condition that American Graphophone would forgo any lawsuit against him for infringing their patents. American Graphophone now owned the Globe Record Company outright, and at the end of 1902 they physically relocated it to Bridgeport, Connecticut, the home of the graphophone plant. About the same time, they substituted the brand name “Columbia Disc Record” for “Climax Record.” Seven-inch specimens of discs from before and after the change are shown below, from my own collection; note that the Climax is one of those with embossed information visible underneath the paper label.

There are no surviving ledgers for early Climax and Columbia discs, as there are for Victor, so it’s been necessary to work out the discography on the basis of catalogs and surviving discs; the authoritative work is the Columbia Master Book Discography by Tim Brooks and Brian Rust, with Tim Brooks being responsible for the early stuff. One mystery Brooks identifies (volume 1, p. 33) is

There are no surviving ledgers for early Climax and Columbia discs, as there are for Victor, so it’s been necessary to work out the discography on the basis of catalogs and surviving discs; the authoritative work is the Columbia Master Book Discography by Tim Brooks and Brian Rust, with Tim Brooks being responsible for the early stuff. One mystery Brooks identifies (volume 1, p. 33) is

why so many low-numbered masters have never been found on Climax, but do turn up later on Columbia. This seems to be more than simply a matter of “we haven’t found them yet.” Whole runs of presumably popular low-numbered recordings do not appear on Climax, among them many early band and orchestra numbers, including no. 1, “In a Clock Store.” Nearly half of the masters in the Climax numerical range (1-826) have not been found on that label, even though virtually all of them turn up on Columbia. The missing numbers are scattered throughout the Climax range.

It is this compiler’s theory that the missing numbers were recorded during the Climax era, but not issued until after the Climax label was discontinued in 1902. Columbia was certainly known to hold recordings for months, or even years, before issuing them. This was especially true of standard repertoire, and it is probably not a coincidence that low-numbered standard selections were most likely to be held for issue on Columbia. Low-numbered topical tunes, on the other hand, usually were quickly released on Climax.

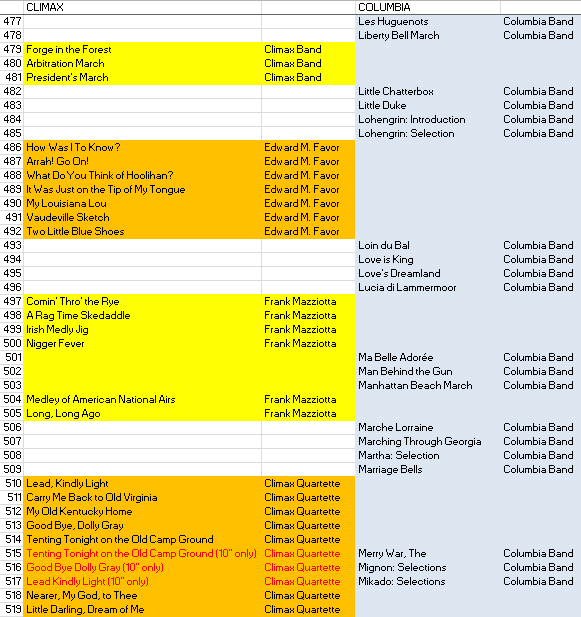

That’s a reasonable hypothesis. However, I want to argue here that the low-numbered items found on Columbia but not Climax are actually another case of “gaps” being filled in, this time in an effort to augment the disc catalog with pieces of “standard repertoire” that Globe had never gotten around to recording but that were central to the Columbia cylinder catalog.

With this in mind, I’ve analyzed the discographic data using much the same approach I took with the early Victor A-series, placing any selection reported on Climax into the left column, and anything else into the right column. The patterns are even clearer than in the case of Victor. The most vivid portion begins at catalog number 284 in the second column, where we find “gaps” in the Climax sequence filled with long runs of alphabetically arranged selections by several performers or ensembles in turn, starting with eighty-six by the Columbia Band (including 322, “Columbia Phonograph Company March”) and then thirty-eight by the Columbia Orchestra. Here’s what the sequence from 477 to 519 looks like: When selections by the “Climax Band” were remade after the acquisition by Columbia, they were credited to the “Columbia Band.” Hence, if the items in the right column had been recorded during the Climax era but not released until later, there should originally have been no distinction between 479-481 and the surrounding selections: they should all have started out as “Climax Band” selections. And yet 479-481 are conspicuously out of alphabetic order relative to the other band recordings in the table, implying that there really was something fundamentally different about them from the start. The only real anomaly here involves the three selections highlighted in red, which seem to have had their catalog numbers reassigned to other selections after the Columbia acquisition. These three selections have been reported on Climax, but only in the ten-inch size; virtually everything else in the Climax catalog appeared on seven and ten-inch discs with the same catalog number in both cases. Moreover, the three selections duplicated selections that had just been assigned other catalog numbers: 515 is the same as 514; 516 is the same as 513; 517 is the same as 510. The same pattern seems to fit most other cases of “duplicate” catalog numbers assigned to one title on Climax and to something different on Columbia; for example, 542 is reported on ten-inch Climax as “The Honeysuckle and the Bee” by Hager’s Orchestra (formerly assigned catalog number 338), but on Columbia as “The Pirates of Penzance” by the Columbia Band. Maybe some of the gaps arose in the Climax sequence due to ten-inch selections being reassigned to corresponding seven-inch catalog numbers.

When selections by the “Climax Band” were remade after the acquisition by Columbia, they were credited to the “Columbia Band.” Hence, if the items in the right column had been recorded during the Climax era but not released until later, there should originally have been no distinction between 479-481 and the surrounding selections: they should all have started out as “Climax Band” selections. And yet 479-481 are conspicuously out of alphabetic order relative to the other band recordings in the table, implying that there really was something fundamentally different about them from the start. The only real anomaly here involves the three selections highlighted in red, which seem to have had their catalog numbers reassigned to other selections after the Columbia acquisition. These three selections have been reported on Climax, but only in the ten-inch size; virtually everything else in the Climax catalog appeared on seven and ten-inch discs with the same catalog number in both cases. Moreover, the three selections duplicated selections that had just been assigned other catalog numbers: 515 is the same as 514; 516 is the same as 513; 517 is the same as 510. The same pattern seems to fit most other cases of “duplicate” catalog numbers assigned to one title on Climax and to something different on Columbia; for example, 542 is reported on ten-inch Climax as “The Honeysuckle and the Bee” by Hager’s Orchestra (formerly assigned catalog number 338), but on Columbia as “The Pirates of Penzance” by the Columbia Band. Maybe some of the gaps arose in the Climax sequence due to ten-inch selections being reassigned to corresponding seven-inch catalog numbers.

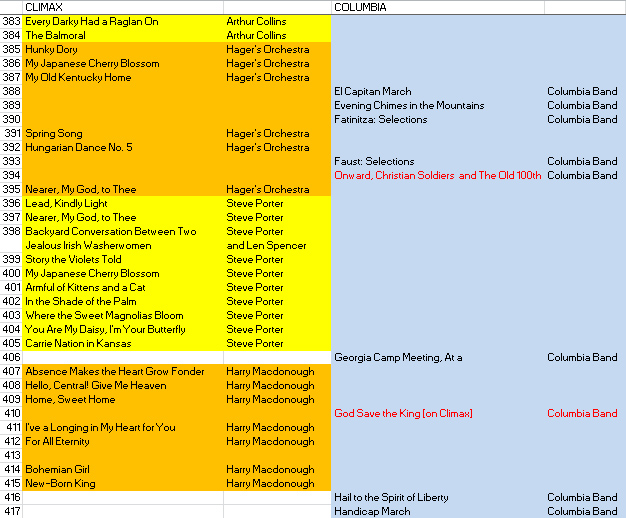

Here’s another piece of the sequence, from 383 to 417:

Number 413 hasn’t turned up on Climax or Columbia, but otherwise there are just two minor anomalies here, marked in red. Number 410, “God Save the King,” has been reported with a Climax label, but by the “Columbia Band,” which suggests that it was recorded during a transitional period—I think it’s reasonable to put it into the right column as a “Columbia” selection. Number 394, “Onward Christian Soldiers and The Old 100th,” seems to be out of alphabetical order, but since it’s a medley of multiple tunes, it might have had some alternate title that fell between “Faust” and “Georgia” (such as “Fellowship Hymn Medley”).

Number 413 hasn’t turned up on Climax or Columbia, but otherwise there are just two minor anomalies here, marked in red. Number 410, “God Save the King,” has been reported with a Climax label, but by the “Columbia Band,” which suggests that it was recorded during a transitional period—I think it’s reasonable to put it into the right column as a “Columbia” selection. Number 394, “Onward Christian Soldiers and The Old 100th,” seems to be out of alphabetical order, but since it’s a medley of multiple tunes, it might have had some alternate title that fell between “Faust” and “Georgia” (such as “Fellowship Hymn Medley”).

It’s easy to imagine how the move to Bridgeport at the end of 1902 might have entailed building new shelving and retrieval systems for matrix storage, and perhaps the scrapping of old, rejected matrices that weren’t worth transporting, either of which could have prompted Columbia to start filling in the numerical gaps. The discovery of this pattern may not reveal a lot about the dates of individual matrices, but I believe it does help us make better sense of the evolution of the Climax/Columbia catalog. If my hypothesis is correct, we can conclude—among other things—that:

- The “Columbia Phonograph Company March” (#322) was never recorded by the Globe Record Company, and so doesn’t provide evidence of a close early relationship between the two companies.

- “In a Clock Store” (#1) wasn’t actually the first Climax recording, an honor that instead goes to “Bohemian Girl” by Edward Franklin (#2).

- The numerous low-numbered German (#108-148) and Hebrew (#150-209) selections were Columbia additions rather than original to the Climax era.

In this blog post, I’ve shown three discographic examples of a “gap-filling” pattern, although in each case the reason behind it appears to be different:

- The New York Phonograph Company needed to replace selections its musicians couldn’t furnish from an earlier North American Phonograph Company catalog with selections they could.

- Eldridge R. Johnson needed to transform a group of numbered “experimental” recordings into the nucleus of a commercial catalog.

- The Columbia Phonograph Company needed to fill some gaps in the Climax Records catalog when they took the product line over from the Globe Record Company—in terms of both selections and catalog numbers.

These may not be earth-shattering findings, but they’re still useful data points in the history of the recording industry, and we can only unearth this kind of information if we’re willing to bring a little creativity and imagination into the world of hardcore discography.

NB. Edison Papers links updated on September 29, 2022.

Pingback: My Fiftieth Griffonage-Dot-Com Blog Post | Griffonage-Dot-Com

Pingback: The First Book of Phonograph Records | ARSC Blog