Two hundred years ago, “Santa Claus” was a woman. At least, that’s the assumption we find being made in a group of writings published in the New-York Evening Post near the close of December 1815, back at a time when the Santa Claus mythos as we know it today was still largely unfixed and unformed. I don’t mean to claim that the average New Yorker of the period necessarily thought Santa Claus was female, but the idea seems at least to have been plausible enough not to get rejected out of hand. In this post, I’ll share the texts themselves and then speculate about how they might fit into a broader history of the Santa Claus tradition. But what’s that you say? “Santa Claus” is just another name for St. Nicholas, who’s obviously male? Well, according to the sources we’ll be examining from 1815, that’s not the case—St. Nicholas was actually Santa Claus’s husband!

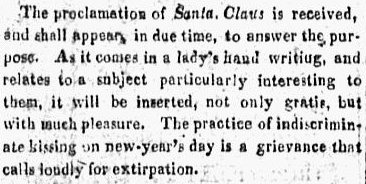

The string of documents began with a brief notice in the New-York Evening Post of December 27, 1815. Like the later installments, it appeared on the second of four pages, which was the most prominent place the editor could have put it—the front page was reserved for paid advertisements.

The proclamation of Santa Claus is received, and shall appear, in due time, to answer the purpose. As it comes in a lady’s hand writing, and relates to a subject particularly interesting to them, it will be inserted, not only gratis, but with much pleasure. The practice of indiscriminately kissing on new-year’s day is a grievance that calls loudly for extirpation.

This sort of notice wasn’t uncommon in newspapers at the time—it simply acknowledged that the editor had received a submission and was planning to publish it but hadn’t had space or time to squeeze it into the current issue. The editor also dangled forth a couple teasers to whet subscribers’ appetites. The submission was supposedly “in a lady’s hand writing”; we never learn the writer’s name, so I’ll just call her Author A. And it was apparently a proclamation from Santa Claus about “indiscriminate kissing on new-year’s day,” a subject the editor thought would be “particularly interesting” to women. Newspapers ordinarily charged money for publishing official notices, but the editor pledged to run this one for free, given its novel source and widespread interest.

The proclamation itself appeared as promised the next day, in the issue for December 28, 1815:

For the New-York Evening Post.

A PROCLAMATION.

Whereas, It has been represented to me that many rude, indecent, vulgar, and ungentlemenlike [sic] old men with or without wigs, married, and unmarried, Batchelors [sic], young men, married or unmarried, being coxcombs or otherwise, and all description of males, have of late years, made it a practice to kiss my subjects, of all sorts, sizes and descriptions, and considering that this vulgar, rude indecent, and ungentlemanlike practice is treating my subjects with rudeness and know it to be disagreable [sic] to some, though not all of them:

NOW THEREFORE, I Santa Clause, Queen and Empress of handsome girls, women married and unmarried, not excepting ugly girls, and old maids of all sorts, phizzes, sizes and descriptions, have thought it proper to issue this my proclamation, commanding, and enjoining all males of all sorts, sizes and descriptions, to desist from this unlawful, indecent, rude, vulgar and ungentleman like [sic] practice from the date of these presents until the fourth of January, 1816; and I hereby further command, that if any male of any sort, size and description be found kissing or attempting to kiss, or making the least advances towards kissing, that he shall be considered hereafter as vulgar, rude, indecent and ungentlemanlike, by all my subjects.—And it is hereby further ordered and commanded, that all my female subjects, of whatever sort, size or description, do give the person so attempting, &c. a hearty box on the left ear, being next to the right hand; and if any of you my subjects submit to any person of the above sort, size or description, the said persons may have it in their power to consider you as deficient in your duty, and to kiss you until your cheeks are filed away by their human files, and not a particle of skin remains.

In testimony whereof, I have caused my seal to be affixed to these presents, and signed the same with my hand. Done in this city of New-York, the 27th day of December, 1815, and the year of my reign the 1717th.

SANTA-CLAUS,

Queen and Empress of the Court of Fashions.

I ran across this “proclamation” on my own, but it has also received a little recent attention elsewhere (in isolation from the other three pieces of the series). John Baker discovered it and brought it up for discussion on Linguistlist on September 7, 2014, in a post with the subject line “Mysterious Early Santa Claus,” writing: “We’ve all heard of Mrs. Claus, but this is the first time I’ve seen Santa Claus referred to as a woman. The item is also quite unusual for its lack of reference to Christmas, though of course its timing was at that time of year.” In fact, Santa Claus (or St. Nicholas, for that matter) wasn’t yet associated closely with Christmas as of 1815, so the lack of reference to that holiday shouldn’t really come as a surprise. Apart from a suggestion that “Santa Claus” might have been a misprint for “Santa Muerte,” there wasn’t any substantive follow-up to the Linguistlist post.

But let’s summarize the main points of the “proclamation.” Santa Claus (here written “Santa-Claus” or “Santa Clause”) is identified as “Queen and Empress” both of the “Court of Fashions” and of women of all descriptions, who are represented as her “subjects.” 1815 is supposedly the 1717th year of her reign, which would have begun circa 98 AD, but she has signed the decree in New York City, suggesting that she’s at home there. She commands men not to kiss her subjects during the following week, which overlaps New Year’s Day, and commands her own subjects in turn to scorn them and strike them on their ears if they try, stipulating that if they don’t, the men are welcome to scour the cheeks of her disobedient subjects raw with their whiskers.

A challenge to Santa Claus’s proclamation appeared in the next issue of the New-York Evening Post, for December 29, 1815, seemingly submitted by a different person whom I’ll call Author B:

For the New-York Evening Post.

IMPERIAL ORDONANCE [sic].

TO ALL WHOM IT MAY CONCERN:

WE, SANCTUS NICHOLAS, Arch-Emperor of the Fashions; LORD PROTECTOR of handsome girls, women, married or unmarried, not excepting ugly girls, and old maids, of all sorts, sizes and phizzes; SOVEREIGN GOVERNOR of old men, married or unmarried, bachelors, young men, married or unmarried, and all description of males, &c. &c. &c. do send this our Imperial Mandate, greeting:

WHEREAS our consort, the Empress “Santa Claus,” has most rebeliously [sic], opprobriously, outrageously and disloyally, endeavored, by a seditious proclamation, to dissuade our most dutiful subjects from their obedience to the most high and sacred authority; and whereas the sovereign sway of our ever-illustrious and ever-memorable ancestors, has, through all ages, been acknowledged supreme; and whereas it has become notorious, that some of our hitherto most loyal subjects have been induced, by the said seditious proclamation, to swerve from their duty; inasmuch as they have expressed their approbation of the innovations therein proposed; and whereas these said innovations, if adopted, will have the pernicious tendency of creating “civil” war among our subjects, of confounding all “social” order, and of bringing to the verge of destruction, customs venerated by our ancestors from time immemorial; and furthermore, whereas no proclamation, in these our wide extended dominions “can” be of any avail, unless sanctioned by our imperial permission; and whereas the said Empress, Santa Claus, has issued the said treasonable proclamation, without our knowledge or sanction:

Now, therefore, we, SANCTUS NICHOLAS, Arch-Emperor of Fashions, &c. &c. do hereby ordain, decree and declare, the said proclamation to be NULL, VOID and of NO EFFECT; and moreover, do offer and proffer, a reward of One Thousand Kisses, to be taken in such portions at a time as best suits her, to any “young” lady, who will give us information of any person that may be convicted of violating this our sovereign decree.

In testimony whereof, we have caused our Imperial Seal to be affixed to these presents, and signed the same with our hand. Done in this city of New-York, the 29th day of December, 1815, in the year of our reign the 2121st.

SANCTUS NICHOLAS.

Author B accepts the claim that “Santa Claus” is female but denies that she has any power to make binding proclamations, instead putting forward her husband “Sanctus Nicholas” as “Sovereign Governor” of all men, “Lord Protector” of all women, and “Arch-Emperor” of fashions—in short, the real possessor of all the authority Santa Claus had claimed for herself, and then some. The Sovereign Governor declares his wife guilty of sedition and treason for encouraging subjects to deviate from their established duties and customs, apparently referring to women who had dared to resist men’s efforts to kiss them on New Year’s Day. In his “ordonance,” Sanctus Nicholas, who has been reigning for 2121 years—i.e., since circa 306 BC, over four centuries years longer than Santa Claus—declares her “proclamation” null and void and promises to reward any young woman who informs him of a violation by kissing her a thousand times.

But that wasn’t to be the end of it. A second communication from Author A followed in the next issue of the New-York Evening Post, for December 30, 1815:

Mr. Editor:

SIR—You will perceive that you are again addressed by the authoress of the first Proclamation, who thanks you very much for inserting it gratis, tho’ she was a little surprised to see yesterday a Proclamation in your paper quite the contrary, and declaring the first one void. I now send you one for publication, which I hope you will condescend to publish, as all the fair sex are concerned, and myself in particular.

If you will put a figure denoting the cost at the end of the Proclamation, it shall be attended to.

IMPERIAL ORDONANCE.

To all whom it may concern.

I, SANCTUS NICHOLAS, Arch Emperor of the fashions, Lord Protector of handsome girls, women married or unmarried, not excepting ugly girls, women married or unmarried, and old maids of all sorts, sizes, phizzes: Sovereign Governor of old men, batchelors [sic], young men, married or unmarried, whether under petticoat government or not, and all description of males, &c. &c. &c. do send this my imperial Mandate, greeting:

Whereas I, Sanctus Nicholas, Arch Emperor, &c. &c. have by my proclamation of yesterday, the 29th, created “civil” war throughout my Imperial Palace, and disturbed the “social” order that heretofore existed in the said Palace, and further, to appease my good, delightful, charming, consort “Santa Claus” who administered to me last night such an agreeable, delightful and entertaining “Curtain Lecture” as has induced me to issue this my proclamation, to prevent the repetition of the same:

Now, therefore, I, SANCTUS NICHOLAS, Arch-Emperor of the Fashions, &c. &c. do hereby declare, ordain and decree, my said proclamation of yesterday, the 29th, to be “NULL, VOID and of NO EFFECT;” moreover, I do hereby declare, ordain and decree, the proclamation of my consort, the Empress “Santa Claus,” to be in full force and effect.

In testimony whereof, I have caused my Imperial Seal to be affixed to these presents, and signed the same with my hand. Done in this city of New-York, the 30th day of December, 1815, and the year of my reign the 2121st.

SANCTUS NICHOLAS.

Approved, SANTA CLAUS.

This is presented as a second “ordonance” from Sanctus Nicholas, but Author A breaks out of frame at the beginning long enough to identify herself as “authoress,” acknowledging that these aren’t real proclamations to be taken at face value. At the same time, she offers to pay for publication this time around if the editor bills her, implying that she still wants the “ordonance” to count as an official notice on some level (which would ordinarily cost something to get printed) rather than merely a piece of submitted commentary or fiction (which wouldn’t). She accepts everything in Author B’s “ordonance,” playing along with its claims just as it had played along with the claims she’d made in the original “proclamation.” However, Santa Claus has since given her husband St. Nicholas a “curtain lecture” (online definition: “an instance of a wife reprimanding her husband in private”), leading him to cancel his “ordonance” in opposition to her proclamation and to admit that he was really the one at fault for fomenting unrest. He has signed his new “ordonance” in the same way as before, but this time Santa Claus has countersigned it as “approved,” suggesting that his decrees are valid and enforceable only if she consents to them.

I suppose it’s possible that Author A and Author B were themselves fictions contrived by a single writer, and that their exchange was a literary artifice. But I’m inclined to take that part of the texts at face value, partly because of stylistic and spelling differences between them (e.g., “batchelors” vs. “bachelors”), and partly because they really seem to be pushing different agendas. The competing decrees deal with a controversial “practice of indiscriminately kissing on new-year’s day” that must have been familiar to New Yorkers of 1815. Author A discourages the practice, while Author B encourages it. And they both invoke authorities and customs of supposedly great antiquity to lend weight to their positions:

- Why shouldn’t men feel free to kiss women on New Year’s Day? Because the venerable Queen Santa Claus has commanded them not to (according to Author A).

- Why can men safely ignore her proclamation? Because the even more venerable Sanctus Nicholas has countermanded it (according to Author B).

But how on earth did “Santa Claus” get drawn into such a role? What information do we really have about popular ideas concerning “Santa Claus” in America in and before 1815?

It’s pretty well known that the name “Santa Claus” is derived from a Dutch colloquial variant of “St. Nicholas” (Sinter Niklaas –> Sinterklaas –> Sante Klaas). This etymology might seem to imply that both names refer to the same (male) person, and in fact they were often stated to be equivalent. However, we should remember that “Kris Kringle” comes from the German Christkindl, or “little Christ child,” demonstrating that the origins of such names don’t necessarily determine how they’re later used and understood. If Kris Kringle (derived from “little Christ child”) can be a grown man, why couldn’t Santa Claus (derived from “St. Nicholas”) be a woman?

As for St. Nicholas himself, it seems that patriotic New Yorkers had first rallied around him in the 1770s as an anti-British counterpart to St. George, and had then latched onto him again around the turn of the century, “rediscovering” him as the old patron saint of the local Dutch community—except that there’s no evidence he had ever actually enjoyed this status (see the article by Charles W. Jones here). Then, around 1810, the New-York Historical Society had set about “reviving” a local tradition in which St. Nicholas brought gifts to children on the eve of his feast day, December 6th, leaving them in stockings hung by the fireplace. This practice resembled an older Dutch tradition in which St. Nicholas put gifts in shoes left by the fireside, but once again, solid evidence of its prior history in North America is lacking. Washington Irving, who was a member of the society, added another detail in the 1812 edition of his fanciful History of New-York, attributed to the fictional Diedrich Knickerbocker: St. Nicholas had a flying wagon in which he rode around over the rooftops to gain access to the chimneys. St. Nicholas also seems to have had a broad association with the end-of-year holiday season in general, since there’s a reference from 1807 in Salmagundi—another publication in which Washington Irving had a hand—to his image having been stamped into New Year’s cookies by bakers back in the heyday of New Netherland. Overall, the rise of St. Nicholas in New York up until 1815 seems to have been rooted in a lot of creative innovations that were passed off, more or less seriously, as faithful revivals of old Dutch ways.

Just a few years after 1815, things finally start to look more familiar. A poem published in 1821 has “Santeclaus” leaving his presents on Christmas Eve rather than on the eve of his own feast day, with reindeer pulling his sleigh (an accompanying illustration shows just one reindeer, but the poem itself is equivocal as to number):

Old SANTECLAUS with much delight

His reindeer drives this frosty night,

O’er chimney-tops, and tracks of snow,

To bring his yearly gifts to you….

Each Christmas eve he joys to come

Where love and peace have made their home.

The famous “Visit from St. Nicholas” made its print debut a couple years later, in December 1823, introducing not only the names of his reindeer, but also the detail that he wasn’t a full-sized human being (remember: “a miniature sleigh, and eight tiny reindeer, / With a little old driver”). As much as that famous poem is supposed to have shaped popular ideas about Santa Claus up to the present day, the detail about Santa’s size didn’t stick.

On the whole, it’s frustratingly unclear how much the written sources people usually cite reflected widespread popular ideas about St. Nicholas or Santa Claus and how much they creatively embellished or even contradicted them. Did the author of “Old Santeclaus” invent the reindeer or just mention a point already widely accepted? Had St. Nicholas flown above American rooftops before Washington Irving? Well, who knows?

The evolution of the name “Santa Claus” itself is equally murky, and this has particular bearing on the question of gender, as we see in a query to an “English Language & Usage” site here:

Santa Claus is a man, right? In this case, he may not be fine with the fact that people call him Santa, which is the Spanish and Portuguese word for female saint names. For example, Santa Barbara and Santa Monica (Barbara and Monica are both female names). Saint Nicholas is by the way translated as San Nicolas and São Nicolas, respectively, in these languages, as San and São are the words for male saint names.

Where does Santa in Santa Claus come from?

The standard reply would be that it comes from Sante Klaas, from Sinterklaas, from Sinter Niklaas, &c. &c. &c. But what was the path to “Santa” specifically?

Many sources cite a first appearance of the name “Santa Claus” as found in Rivington’s Gazetteer (New York City) of December 23, 1773: “Last Monday, the anniversary of St. Nicholas, otherwise called Santa Claus, was celebrated at Protestant Hall, at Mr. Waldron’s; where a great number of sons of the ancient saint the Sons of St. Nicholas celebrated the day with great joy and festivity.” The passage was already being quoted in that form in New Amsterdam Gazette for October-November 1892. But other sources quote the same source as reading “St. A. Claus” (here), “St. A Claus” (the online Oxford English Dictionary), “St. a Claus” (here), and even “Santa the Claus” (here). So who’s right? The full name of the newspaper in question was Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, or, the Connecticut, New-Jersey, Hudson’s-River, and Quebec Weekly Advertiser, and with that information in hand, I hunted down a scan of the original. It turns out to read “St. a Claus”:

The alternate name of Saint Nicholas in 1773 was thus apparently “Saint a Claus”—not “Santa Claus” in its later form, and definitely not “Saint A. Claus” (punctuated as though the “A” were an abbreviation for a name). The next appearance of a Santa Claus-like name is in Salmagundi, Jan 25, 1807, page 405, where we read of “the noted St. Nicholas, vulgarly called Santaclaus—of all the saints in the kalendar [sic] the most venerated by true hollanders [sic], and their unsophisticated descendants.”

The alternate name of Saint Nicholas in 1773 was thus apparently “Saint a Claus”—not “Santa Claus” in its later form, and definitely not “Saint A. Claus” (punctuated as though the “A” were an abbreviation for a name). The next appearance of a Santa Claus-like name is in Salmagundi, Jan 25, 1807, page 405, where we read of “the noted St. Nicholas, vulgarly called Santaclaus—of all the saints in the kalendar [sic] the most venerated by true hollanders [sic], and their unsophisticated descendants.”

This passage, in a periodical directed by Washington Irving, mentions St. Nicholas’s image being stamped on New Year’s cookies in old Dutch New York. St. Nicholas also comes up a lot in Irving’s History of New-York, but never by any name resembling “Santa Claus.”

This passage, in a periodical directed by Washington Irving, mentions St. Nicholas’s image being stamped on New Year’s cookies in old Dutch New York. St. Nicholas also comes up a lot in Irving’s History of New-York, but never by any name resembling “Santa Claus.”

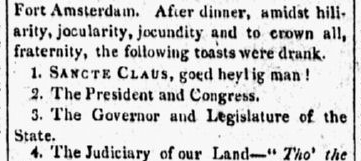

Then, in December 1810, a bilingual poem “SANCTE CLAUS, goed heylig Man! / SAINT NICHOLAS, good holy man!” was published with a woodcut by Alexander Anderson, more or less under the auspices of the New-York Historical Society. “Sancte Claus” seems to have been the society’s preferred spelling of the Dutch name of St. Nicholas, as shown in a report of toasts drunk at its Festival of St. Nicholas on December 6, 1810 (published in the New York Commercial Advertiser of December 11):

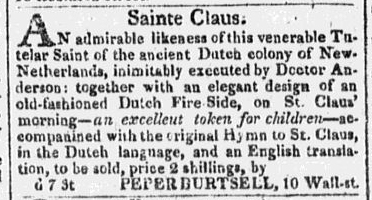

However, the New-York Gazette & General Advertiser promoted Anderson’s woodcut on December 7th with the spelling “Sainte Claus,” alternating with “St. Claus”:

However, the New-York Gazette & General Advertiser promoted Anderson’s woodcut on December 7th with the spelling “Sainte Claus,” alternating with “St. Claus”:

Next, a reference to “Santaclaw” is often cited as appearing in the 1813 first edition of False Stories Corrected, published by Samuel Wood. I haven’t seen the 1813 edition, but I found the quoted passage in the 1814 edition, on pages 40-41, as part of a section debunking Jack Frost:

Next, a reference to “Santaclaw” is often cited as appearing in the 1813 first edition of False Stories Corrected, published by Samuel Wood. I haven’t seen the 1813 edition, but I found the quoted passage in the 1814 edition, on pages 40-41, as part of a section debunking Jack Frost:

[S]uch a creature as Jack Frost never existed, any more than old Santaclaw, of whom so often little children hear such foolish stories; and once in the year are encouraged to hang their stockings in the chimney at night, and when they arise in the morning, they find in them cakes, nuts, money, &c. placed there by some of the family, which they are told Old Santaclaw has come down chimney in the night and put in. Thus the little innocents are imposed on by those who are older than they, and improper ideas take possession which are not by any means profitable.

This passage also appeared in the 1815 edition, but it had been cut from the 1817 edition, and it’s also missing from the 1822 edition freely available online—the later editions state simply that “such a creature as Jack Frost never existed” and leave it at that. Maybe there had been complaints from unhappy parents.

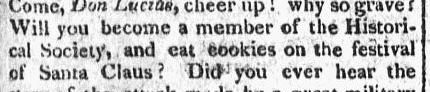

So we have “St. a Claus” (1773), “Santaclaus” (1807), “Sancte Claus” (1810), “Sainte Claus” (1810), “St. Claus” (1810), and “Santaclaw” (1813). But what about “Santa Claus,” with that exact spelling and spacing? As far as I can tell, nobody has tried very hard to find its first appearance, maybe because the other versions have seemed close enough to it to count. But I’ve tried to pin down this data point myself, and the earliest instance of it I’ve turned up appears in the New York Columbian of January 14, 1811: “Will you become a member of the Historical Society, and eat cookies on the festival of Santa Claus?”

The “festival of Santa Claus” was, of course, December 6th—not Christmas. This new (?) variant of the name was the first to resemble familiar Spanish and Portuguese designations for female saints: Santa Maria, Santa Barbara, and so forth. Granted, sainte is also the French word for a female saint, but I suspect that the e in “Sainte Claus” was supposed to be pronounced, unlike the e in the French word, so there may have been less cause for gender confusion in that case. When the series of letters about new-year’s kissing appeared in the New-York Evening Post in December 1815, then, “Santa Claus” wasn’t yet the established version of the name it later became—indeed, this was only the second instance I could find of the name appearing in that form, after the one in 1811. (The first letter technically gave the name as “Santa Clause” and “Santa-Claus” with a hyphen, but it was consistently “Santa Claus” on December 27, 29, and 30.) I doubt it was mere coincidence that Author A had adopted the rare version of the name that best supported her effort to recast the supreme authority figure of the end-of-year holiday season as a woman.

The “festival of Santa Claus” was, of course, December 6th—not Christmas. This new (?) variant of the name was the first to resemble familiar Spanish and Portuguese designations for female saints: Santa Maria, Santa Barbara, and so forth. Granted, sainte is also the French word for a female saint, but I suspect that the e in “Sainte Claus” was supposed to be pronounced, unlike the e in the French word, so there may have been less cause for gender confusion in that case. When the series of letters about new-year’s kissing appeared in the New-York Evening Post in December 1815, then, “Santa Claus” wasn’t yet the established version of the name it later became—indeed, this was only the second instance I could find of the name appearing in that form, after the one in 1811. (The first letter technically gave the name as “Santa Clause” and “Santa-Claus” with a hyphen, but it was consistently “Santa Claus” on December 27, 29, and 30.) I doubt it was mere coincidence that Author A had adopted the rare version of the name that best supported her effort to recast the supreme authority figure of the end-of-year holiday season as a woman.

Author B conceded that “Santa Claus” was female. But that implied that St. Nicholas, the man, had to be someone else. When drawing this other holiday figure into the argument on the other side, Author B emphasized his masculinity by using a conspicuously gendered Latin word: he wasn’t just St. Nicholas, but Sanctus Nicholas. This gesture, too, points to “Santa” being recognized by contrast as feminine.

Maybe the exchange in the New-York Evening Post was an isolated oddity that doesn’t tell us anything significant about Santa’s history. But maybe, just maybe, it preserves some vestige of an alternative, more flexible perspective—one in which the gender of “Santa Claus” had been irrelevant or up for grabs, like the gender of the Easter Bunny, and in which the separately-written word “Santa” was still new enough to conjure up associations with the names of female saints. After all, the average New Yorker of 1815 might have known “Santa Claus” mainly as a name the men of the New-York Historical Society were trying to associate locally with a set of newly-invented “old” December traditions, without being particularly aware of the details. And if those men were seen to be shaping the “Santa Claus” mythos at will, why couldn’t someone else have felt free to do the same thing—a lady, for instance, who wanted to assume the voice of a holiday-season authority for her attack on an obnoxious New Year’s Day practice?

Two hundred years ago, “Santa Claus” might still have been enough of a blank slate to become whatever anyone wanted him—or her—to be.

Pingback: My Fiftieth Griffonage-Dot-Com Blog Post | Griffonage-Dot-Com