No, I don’t mean pictures of people playing table tennis. During the first quarter of the twentieth century, the “ping pong” was one of the cheapest and most popular types of photograph in America. But chances are you’ve never heard of it. The very term “ping pong,” in its photographic sense, has now fallen into such disuse that it’s hard to find even passing modern-day references to it.

The pictures themselves turn up constantly, though, and they can’t help but attract notice, whether they take the form of flimsy paper photo strips or tiny single images. At their best, they share many of the most beloved characteristics of the tintype with which they shared their popularity for a time. We see subjects goofing around, interacting with a conventionalized set of props, experimenting with moods and identities and costumes, reveling in the sheer fun of having their pictures taken.

The pictures themselves turn up constantly, though, and they can’t help but attract notice, whether they take the form of flimsy paper photo strips or tiny single images. At their best, they share many of the most beloved characteristics of the tintype with which they shared their popularity for a time. We see subjects goofing around, interacting with a conventionalized set of props, experimenting with moods and identities and costumes, reveling in the sheer fun of having their pictures taken.

But unlike tintypes, which were almost always cut apart when multiple images were captured on a single plate, “ping pongs” often present intact sequences of two, three, four, five, six, or more shots neatly arranged in the order in which they were taken, sometimes just because purchasers never got around to cutting them up, but sometimes because they considered a sequence attractive enough in its own right for them to paste it into an album or have it mounted on a card “as is.”

But unlike tintypes, which were almost always cut apart when multiple images were captured on a single plate, “ping pongs” often present intact sequences of two, three, four, five, six, or more shots neatly arranged in the order in which they were taken, sometimes just because purchasers never got around to cutting them up, but sometimes because they considered a sequence attractive enough in its own right for them to paste it into an album or have it mounted on a card “as is.”

And no wonder: for many people, this would have been the first time-based visual record they’d ever participated in making, and the first they actually owned.

And no wonder: for many people, this would have been the first time-based visual record they’d ever participated in making, and the first they actually owned.

Wait a minute, you might be thinking: aren’t these just photobooth pictures? It’s true that most similar photo strips created over the past ninety years have come out of self-service photobooths. But for a quarter century before that, they were instead the exclusive domain of live “ping pong artists,” whose work was disdained at the time by the rest of the photographic profession and has been almost wholly forgotten today. This lack of recognition is unfortunate. The older “ping pong” deserves more understanding and appreciation than it’s received, and its rehabilitation as an object of interest is long overdue. This essay is intended as one step in that direction. Unless stated otherwise, all of the “ping pongs” shown here are drawn from my own collection.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines ping pong as “the game of table tennis” (1900) and by extension “a series of rapid (esp. verbal) exchanges between two things or parties” (1909); or, as a verb, “to send or pass back and forth in the manner of a ping-pong ball” (1902). “Ping pong” in the sense of table tennis had reached the United States as an imported English fad in 1901-1902, and the term was being used metaphorically in short order: witness the headline “Stock Exchange Ping-Pong” in the Biloxi, Mississippi Daily Herald for October 11, 1901. This was the context, then, in which the name “ping pong” came to be applied to a novel development in photography. According to a post at graflexcamera.tumblr.com, a “ping pong” camera was one with a sliding frame that ping-ponged back and forth and allowed photographers quickly and easily to take multiple images on a single plate with their number, spacing, and placement controlled by detachable rods. In this way, each negative plate could be made to hold multiple image sequences, as illustrated below by a rare uncut print which would ordinarily have been cut into three strips before delivery.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines ping pong as “the game of table tennis” (1900) and by extension “a series of rapid (esp. verbal) exchanges between two things or parties” (1909); or, as a verb, “to send or pass back and forth in the manner of a ping-pong ball” (1902). “Ping pong” in the sense of table tennis had reached the United States as an imported English fad in 1901-1902, and the term was being used metaphorically in short order: witness the headline “Stock Exchange Ping-Pong” in the Biloxi, Mississippi Daily Herald for October 11, 1901. This was the context, then, in which the name “ping pong” came to be applied to a novel development in photography. According to a post at graflexcamera.tumblr.com, a “ping pong” camera was one with a sliding frame that ping-ponged back and forth and allowed photographers quickly and easily to take multiple images on a single plate with their number, spacing, and placement controlled by detachable rods. In this way, each negative plate could be made to hold multiple image sequences, as illustrated below by a rare uncut print which would ordinarily have been cut into three strips before delivery.

The same graflexcamera.tumblr.com post also quotes a 1902 advertisement for the Century Penny Picture Camera, introduced in 1900: “The back is made to slide both vertically and horizontally and permits making one, two, four, six, eight, twelve, sixteen or twenty-four exposures on the same 5 x 7 plate…. By setting the rod in advance for the spacing desired, the sliding back will register without further attention, by moving to successive holes, as indicated by the clicks.” Another advertisement for the same camera is shown on the right.

The same graflexcamera.tumblr.com post also quotes a 1902 advertisement for the Century Penny Picture Camera, introduced in 1900: “The back is made to slide both vertically and horizontally and permits making one, two, four, six, eight, twelve, sixteen or twenty-four exposures on the same 5 x 7 plate…. By setting the rod in advance for the spacing desired, the sliding back will register without further attention, by moving to successive holes, as indicated by the clicks.” Another advertisement for the same camera is shown on the right.

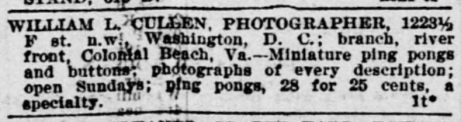

Once such sliding-back cameras had entered widespread use, the name “ping pong” also came to be used for photographs made with them. The earliest instance I’ve turned up of this usage appears in an advertisement for photographer William L. Cullen in the Washington Evening Star of November 21, 1903, p. 24, who assumed readers would already know what a “ping pong” was:

WILLIAM L. CULLEN, PHOTOGRAPHER, 1223½ F st. n.w., Washington, D. C.; branch, river front, Colonial Beach, Va.—Miniature ping pongs and buttons, photographs of every description; open Sundays; ping pongs, 28 for 25 cents, a specialty.

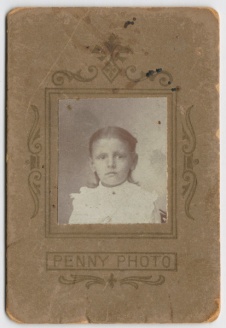

Within a few years of Cullen’s advertisement, references to “ping pong pictures,” “ping pong photos,” and “ping pong cameras” had become commonplace. During the same period, the term “penny photo” (or “penny picture”) often seems to have been used interchangeably with “ping pong,” but we sometimes also find a distinction being drawn between the two types, with “ping pong” being applied more specifically to an unmounted strip of images of varied poses and “penny photo” to a mounted print of a single portrait furnished in bulk (see example at left). This would make sense, given that the ping-ponging action that gave the “ping pong” its name would only have taken place when a photographer was capturing a sequence of images in a row.

Within a few years of Cullen’s advertisement, references to “ping pong pictures,” “ping pong photos,” and “ping pong cameras” had become commonplace. During the same period, the term “penny photo” (or “penny picture”) often seems to have been used interchangeably with “ping pong,” but we sometimes also find a distinction being drawn between the two types, with “ping pong” being applied more specifically to an unmounted strip of images of varied poses and “penny photo” to a mounted print of a single portrait furnished in bulk (see example at left). This would make sense, given that the ping-ponging action that gave the “ping pong” its name would only have taken place when a photographer was capturing a sequence of images in a row.

Today, “ping pongs” are routinely mistaken for the products of automated photobooths, which they closely resemble. The first automated photobooth to take, develop, and spit out strips of multiple images taken in rapid succession was the Photomaton invented by Anatol Josepho in 1925. Automated photo machines had existed before then, but as far as I’m aware—and I’ve hunted far and wide for counterexamples—these had all been designed to take and process only one image at a time. Josepho’s device surely owed its success in part to strictly mechanical advantages it enjoyed over its precursors, but it was also distinctive for the specific photographic genre it aimed to automate. We read in Automatic Age (May 1927): “Josepho conceived the idea of the machine when he had a small studio in China and eked out a bare existence by making cheap ‘ping pong’ pictures of the natives.” Thus, the Photomaton wasn’t merely an automated photobooth; it was an automated photobooth designed specifically to produce the “ping pong” strips with which both Josepho and the general public were already familiar. It didn’t introduce a new photographic commodity, but only made the production of an existing one cheaper, more efficient, and more of a mechanical novelty than it had been before. In terms of their form, style, content, and overall aesthetics, then, I’d argue that photobooth strips are better understood as a continuation of the “ping pong” tradition than as an outgrowth of earlier coin-in-the-slot photography. That said, it’s hard to talk about the broader genre to which they both belong for want of appropriate language. On the one hand, the older strips weren’t produced in photobooths, so they can’t be called “photobooth” strips; and on the other hand, photobooth machines don’t have any visible part that ping-pongs back and forth, so it would seem odd to refer to their products as “ping pongs.” “Penny picture” refers to an epiphenomenal matter of pricing. “Photo strip” is an attractive option, and I’ve already used it myself earlier in this essay, but I’m not sure the strip format itself should necessarily be our central defining feature. Take the specimen shown below, captioned “Tilly Williams 1898” on the back (if I’m reading it correctly).

In terms of their form, style, content, and overall aesthetics, then, I’d argue that photobooth strips are better understood as a continuation of the “ping pong” tradition than as an outgrowth of earlier coin-in-the-slot photography. That said, it’s hard to talk about the broader genre to which they both belong for want of appropriate language. On the one hand, the older strips weren’t produced in photobooths, so they can’t be called “photobooth” strips; and on the other hand, photobooth machines don’t have any visible part that ping-pongs back and forth, so it would seem odd to refer to their products as “ping pongs.” “Penny picture” refers to an epiphenomenal matter of pricing. “Photo strip” is an attractive option, and I’ve already used it myself earlier in this essay, but I’m not sure the strip format itself should necessarily be our central defining feature. Take the specimen shown below, captioned “Tilly Williams 1898” on the back (if I’m reading it correctly).

The frames are clearly organized here into some kind of chronological order, although the exact sequence isn’t obvious to me—maybe top left to bottom left, then bottom middle to top middle, then top right to bottom right? If someone had cut this same print into strips, each one would pass as a “ping pong,” even though that term wasn’t yet in use when it was made. But even as a time-based photo matrix, it still strikes me as a thing of the same type we’ve been examining. And that type might best be defined as a subcategory of image sequence photography that’s meant to provide a consistently attractive variety of chronologically ordered poses (rather than, say, to offer scientific insights into how natural motion works, to sustain a moving-picture illusion through “playback,” or to capture several wholly independent shots from which only the best will be singled out for further use).

The frames are clearly organized here into some kind of chronological order, although the exact sequence isn’t obvious to me—maybe top left to bottom left, then bottom middle to top middle, then top right to bottom right? If someone had cut this same print into strips, each one would pass as a “ping pong,” even though that term wasn’t yet in use when it was made. But even as a time-based photo matrix, it still strikes me as a thing of the same type we’ve been examining. And that type might best be defined as a subcategory of image sequence photography that’s meant to provide a consistently attractive variety of chronologically ordered poses (rather than, say, to offer scientific insights into how natural motion works, to sustain a moving-picture illusion through “playback,” or to capture several wholly independent shots from which only the best will be singled out for further use). I don’t think there’s any agreed-upon name for the kind of photograph I’ve just described, and that’s had an unfortunate effect. Because there’s no widely recognized category which pictures like these all share in common, “ping pongs” have usually been treated in practice as faux photobooth images—characterized, like fool’s gold or false morels, more in terms of what they aren’t than in terms of what they are. Photobooth pictures are the really interesting thing here, the message seems to run. Those older photo strips may look a lot like them, but don’t be deceived: they’re not the genuine article, and they shouldn’t interest us in the same way. Nobody puts it quite like that, of course. But in American Photobooth (2008), Näkki Goranin writes (pp. 42-44):

I don’t think there’s any agreed-upon name for the kind of photograph I’ve just described, and that’s had an unfortunate effect. Because there’s no widely recognized category which pictures like these all share in common, “ping pongs” have usually been treated in practice as faux photobooth images—characterized, like fool’s gold or false morels, more in terms of what they aren’t than in terms of what they are. Photobooth pictures are the really interesting thing here, the message seems to run. Those older photo strips may look a lot like them, but don’t be deceived: they’re not the genuine article, and they shouldn’t interest us in the same way. Nobody puts it quite like that, of course. But in American Photobooth (2008), Näkki Goranin writes (pp. 42-44):

In the same time period [as various attempts to create automated, self-service photo machines], 1895 through 1925, other photos that today are mistaken for early photobooth shots were actually done in multiple strips on portions of a five-by-seven negative-plate Penny Camera. These photos had two popular names. Called “penny photos” or “ping pong photos,” they were cheaply done and available in penny arcades or photo studios. Usually made in horizontal strips, they closely resemble photobooth strips. Josepho, in his studio in Shanghai, made a large part of his income from penny photos. They remained popular until the late 1920s when the easy accessibility of photobooths ended this style of photography.

To me, the close resemblance observed by Goranin instead suggests that the same “style” of photography continued well beyond the 1920s, and that its creation was simply relocated to photobooths. Even for someone who’s familiar with the distinction, it can be hard to tell “ping pongs” taken by live photographers from photobooth strips. Some clues can be used to identify a “ping pong”: if backgrounds aren’t consistent with the interior of a photobooth, or if the edges of adjacent images taken on the same plate are visible, or if changes in costume, props, or orientation imply a longer gap in time between shots. But there are few clues that point conclusively in the opposite direction, other perhaps than details of fashion that place a strip well into the 1930s or beyond. It’s not uncommon to find a definite “ping pong” with a curtain as its background, so that in itself doesn’t count as evidence of photobooth origin. The example below is captioned “Gladys Geier 1922,” three years before the birth of the Photomaton.

Elsewhere in her book, Goranin shows four examples of older “penny photo” strips but captions them as “taken by turn-of-the-century automatic photo machines or penny cameras,” while the accompanying text refers to a machine “put out by General Electric” that was “introduced in American and Canadian penny arcades and produced ‘penny photos'” (p. 18). I assume she must be referring to the Auto-Foto machines introduced circa 1912, which were manufactured by General Electric, but these were only designed to process a single image at a time and so shouldn’t have produced anything like “ping pongs.” Overall, Goranin seems to want to downplay any evidence that the cultural form she’s writing about might date back before self-service automation and the privacy and license that came with it. In her account, either the earlier strips represent a different “style of photography” that died out, or else it’s left ambiguous whether they were produced automatically or by hand.

Elsewhere in her book, Goranin shows four examples of older “penny photo” strips but captions them as “taken by turn-of-the-century automatic photo machines or penny cameras,” while the accompanying text refers to a machine “put out by General Electric” that was “introduced in American and Canadian penny arcades and produced ‘penny photos'” (p. 18). I assume she must be referring to the Auto-Foto machines introduced circa 1912, which were manufactured by General Electric, but these were only designed to process a single image at a time and so shouldn’t have produced anything like “ping pongs.” Overall, Goranin seems to want to downplay any evidence that the cultural form she’s writing about might date back before self-service automation and the privacy and license that came with it. In her account, either the earlier strips represent a different “style of photography” that died out, or else it’s left ambiguous whether they were produced automatically or by hand.

If critics find photobooth pictures appealing in part because of the unsupervised settings in which they’re made, then it’s easy to see why they might want to exclude “ping pongs” shot by live photographers from consideration as part of the same category. But true privacy may not actually have entered the picture until after photobooths themselves had already been around for quite a while, judging from Babbette Hines’s remarks in Photobooth (2002):

If critics find photobooth pictures appealing in part because of the unsupervised settings in which they’re made, then it’s easy to see why they might want to exclude “ping pongs” shot by live photographers from consideration as part of the same category. But true privacy may not actually have entered the picture until after photobooths themselves had already been around for quite a while, judging from Babbette Hines’s remarks in Photobooth (2002):

The earliest photobooth pictures, those from the late 1920s, often retained some of the studied formality of studio portraits. The subjects of these portraits dutifully obeyed the commands of the attendant without, apparently, a great deal of pleasure. They glanced left, they glanced right, and they stared straight ahead. Although often smiling, they frequently looked a bit wary, sometimes even grim. By the 1930s, however, more familiar expressions began to appear. Faces and postures relaxed, the smiles weren’t quite as forced, people began to shed their inhibitions. More than likely, this development coincided with the removal of the attendant, allowing the solitude we now take for granted and cherish. Perhaps it is only in solitude that we are free to decide which face to present to the camera, which story we want to tell.

The first “fully automated” photobooths were prone to breaking down, which is why attendants had to remain close at hand to oversee their operation. I’m not sure these attendants would have issued any specific “commands” for subjects to “obey” while having their pictures taken; instead, I imagine them intervening only when something went awry mechanically. However, their very presence might be seen as blurring the line between photo strips shot under supervised and unsupervised conditions. Whether there was a causal relationship between the removal of the photobooth attendant and the progressive shedding of inhibitions, as Hines speculates, is another question. It makes intellectual sense that there could have been. But there are also plenty of fully supervised “ping pongs” in which the subject doesn’t look particularly inhibited to my eye.

Hines may well be right that the typical photobooth expression underwent a change during the 1930s, but if she is, I suspect the trend may have owed less to the disappearance of the photobooth attendant than it did to a broader shift in the culture of portrait photography. As I’ve shown elsewhere, the convention of smiling for high school yearbook portraits only took root about the same time, between the late 1920s and the late 1930s. Smiling for the camera is a culturally learned behavior, and not something we naturally fall into by default if a photographer isn’t prompting us to look serious. People who are “free to decide which face to present to the camera” don’t necessarily smile, nor does everyone necessarily want to tell the same “story.”

Hines may well be right that the typical photobooth expression underwent a change during the 1930s, but if she is, I suspect the trend may have owed less to the disappearance of the photobooth attendant than it did to a broader shift in the culture of portrait photography. As I’ve shown elsewhere, the convention of smiling for high school yearbook portraits only took root about the same time, between the late 1920s and the late 1930s. Smiling for the camera is a culturally learned behavior, and not something we naturally fall into by default if a photographer isn’t prompting us to look serious. People who are “free to decide which face to present to the camera” don’t necessarily smile, nor does everyone necessarily want to tell the same “story.”

I don’t mean to deny that an important change took place in the dynamics of photo strip production at some point between the 1910s and the 1930s. In the 1910s, a photographer would always have been present to coach subjects through the shoot and to recommend different poses or interactions. Fold your hands behind your head. Pick up that mirror and look into it. Try on one of these hats. By the 1930s, subjects would instead have been on their own when deciding what to do. But most of the patrons of the first photobooths would also have patronized “ping pong artists” in the past and would probably have internalized the instructions they’d then received to at least some degree. I doubt self-service automation brought about any sharp or sudden discontinuity in poses or expectations.

I don’t mean to deny that an important change took place in the dynamics of photo strip production at some point between the 1910s and the 1930s. In the 1910s, a photographer would always have been present to coach subjects through the shoot and to recommend different poses or interactions. Fold your hands behind your head. Pick up that mirror and look into it. Try on one of these hats. By the 1930s, subjects would instead have been on their own when deciding what to do. But most of the patrons of the first photobooths would also have patronized “ping pong artists” in the past and would probably have internalized the instructions they’d then received to at least some degree. I doubt self-service automation brought about any sharp or sudden discontinuity in poses or expectations.

That said, preconceptions about privacy can be a significant source of error when it comes to interpreting early photo strips today. Thus, we sometimes find specific “ping pongs” being misread on the assumption that all photo strips were taken under unsupervised conditions. Consider the following passage from one article about “photobooth selfies”:

This selection of women taking pictures, reveals how the privacy of the booth allowed people to express themselves—as can be seen in the pictures of two women sharing their love for each other, circa 1900s, when such signs of affection were not permissible.

The images in question come from the blog of Walter Plotnick, who had posted them (apparently as part of a four-frame animated GIF, although his original link is now dead) with a similar description: “Ultra rare 1900’s photos of women – lovers kissing in early photobooth…from my archive.” However, one of Plotnick’s readers commented: “If you look at Nakki Goranin’s history of photobooth technology you will see that these pics don’t fit into that genre.” On closer examination, it’s plain that they weren’t taken in an automatically operated booth, and that a live “ping pong artist” must have taken them instead. The subjects of images such as these, or the picture of two women rubbing noses shown at right, must have been less covert about their shows of intimacy than some commentators suppose. But it strikes me that the question of genre boundaries (“these pics don’t fit into that genre”) is less straightforward. Plotnick’s images may not be “photobooth selfies” as billed, and that’s an important point when it comes to weighing their transgressive character, but they’re still photo-strip images in what I’d argue is the same tradition. As far as agency goes, it’s also unlikely that the women were prompted to kiss or rub noses by the photographer. And for that matter, I wonder whether the patrons of the first photobooths really thought of the results as self-portraits or machine portraits—pictures taken by robot.

The images in question come from the blog of Walter Plotnick, who had posted them (apparently as part of a four-frame animated GIF, although his original link is now dead) with a similar description: “Ultra rare 1900’s photos of women – lovers kissing in early photobooth…from my archive.” However, one of Plotnick’s readers commented: “If you look at Nakki Goranin’s history of photobooth technology you will see that these pics don’t fit into that genre.” On closer examination, it’s plain that they weren’t taken in an automatically operated booth, and that a live “ping pong artist” must have taken them instead. The subjects of images such as these, or the picture of two women rubbing noses shown at right, must have been less covert about their shows of intimacy than some commentators suppose. But it strikes me that the question of genre boundaries (“these pics don’t fit into that genre”) is less straightforward. Plotnick’s images may not be “photobooth selfies” as billed, and that’s an important point when it comes to weighing their transgressive character, but they’re still photo-strip images in what I’d argue is the same tradition. As far as agency goes, it’s also unlikely that the women were prompted to kiss or rub noses by the photographer. And for that matter, I wonder whether the patrons of the first photobooths really thought of the results as self-portraits or machine portraits—pictures taken by robot.

In Photobooth: The Art of the Automatic Portrait (2010, pp. 19-27), Raynal Pellicer is more forthright about acknowledging manually created photo strips as precursors of the photobooth strip, but he limits his account to examples with a studio address and serial number displayed at the top of the frame, including the Sticky Backs produced in Brighton, England, by Spiridione Grossi (described in more detail at photohistory-sussex.co.uk) and some similarly formatted French items. The Sticky Back was a cross between the “ping pong” and the photo stamp with adhesive backing, which had its own prior history, and it’s unclear to me whether the other examples Pellicer cites were also sticky. In any case, I’ve run across very few American “ping pongs” that display a studio address and serial number—the example shown on the left is a rare exception, and apparently nonadhesive—so Pellicer’s emphasis on this detail seems a little misleading in the context of the United States.

In Photobooth: The Art of the Automatic Portrait (2010, pp. 19-27), Raynal Pellicer is more forthright about acknowledging manually created photo strips as precursors of the photobooth strip, but he limits his account to examples with a studio address and serial number displayed at the top of the frame, including the Sticky Backs produced in Brighton, England, by Spiridione Grossi (described in more detail at photohistory-sussex.co.uk) and some similarly formatted French items. The Sticky Back was a cross between the “ping pong” and the photo stamp with adhesive backing, which had its own prior history, and it’s unclear to me whether the other examples Pellicer cites were also sticky. In any case, I’ve run across very few American “ping pongs” that display a studio address and serial number—the example shown on the left is a rare exception, and apparently nonadhesive—so Pellicer’s emphasis on this detail seems a little misleading in the context of the United States.

A visit to a “ping pong artist” was such a common experience during the first quarter of the twentieth century that few people bothered to describe it at the time, either in words or in images. Some people still alive in 2017 must remember what it was like, if any oral historians are looking for good questions to pose to centenarians. As it stands, though, the best existing description I’ve found of a “ping pong” photographer in action appeared in the Kansas City Star for March 1, 1908:

A PING PONG ARTIST AT WORK.

Here is a Photographer Who Can Handle His Subjects.With no attention to giggles or whispers or exclamations from his subjects, the picture postal and “ping pong photo” man kept steadily at his work. Saturday is his busy day.

“Still, please!”

Click!

“That’s all. Next!”

The “next” was a woman with a baby. But the “ping pong” artist wasn’t disturbed by the baby, as photographers sometimes are.

“With his cap on, ma’am? Good. Look sharp. I’m ready.”

Three times the photographer whistled and then:

“Tr-r-r-r! Tr-r-r-r!”

The “ping pong” man really didn’t have to trill, but he did just to be doubly sure of a “look pleasant” expression.

Click! Click! Click!

“That’s all, ma’am. Next!”

A plump, red-cheeked girl holding hands with a bashful young man, marched resolutely before the screen.

“Want the picture double, Miss?”

“Yes, sir, please,” the maid replied.

“Take ’em together an’ it’s twenty cents,” the bulb presser said.

“That’s all right,” the young man interrupted. “Go right ahead. I’m good for the extra charge.”

“Sit close together.”

The command was obeyed promptly.

“Still, please!”

“There’s one! Now, again! St-i-ll! Once more! That’s all!”

Then the “ping pong” man turned to the visitor and smiled.

“These young lovers are great fun,” he said. “I have fun with people, if I am busy. ‘Grin and hustle,’ that’s my motto. I have as much to do as anyone else. I make 75,000 to 100,000 pictures in one month. I made 960 last Saturday. Great! I take three positions at ten cents a dozen—three positions in forty seconds. I wear out one camera every year.”

The photographer in this account seems to be capturing shots in groups of three: “Click! Click! Click!” His surcharge for photos “taken double” rings true (one advertisement for penny pictures in the Hartford (Kentucky) Republican of February 19, 1909, similarly states: “Prices 24 for 25c. Extra faces 10c.”). The stated figure of 75,000 to 100,000 pictures per month seems quite plausible too (one Phoenix studio claimed in the Arizona Republican of March 3, 1918, to have taken a staggering 480,000 photographs since January 15th). This particular “ping pong” artist is also associated with “picture postals,” which are generally known today as real photo post cards, and which likewise fell on the cheap end of the price spectrum.

The photographer in this account seems to be capturing shots in groups of three: “Click! Click! Click!” His surcharge for photos “taken double” rings true (one advertisement for penny pictures in the Hartford (Kentucky) Republican of February 19, 1909, similarly states: “Prices 24 for 25c. Extra faces 10c.”). The stated figure of 75,000 to 100,000 pictures per month seems quite plausible too (one Phoenix studio claimed in the Arizona Republican of March 3, 1918, to have taken a staggering 480,000 photographs since January 15th). This particular “ping pong” artist is also associated with “picture postals,” which are generally known today as real photo post cards, and which likewise fell on the cheap end of the price spectrum.

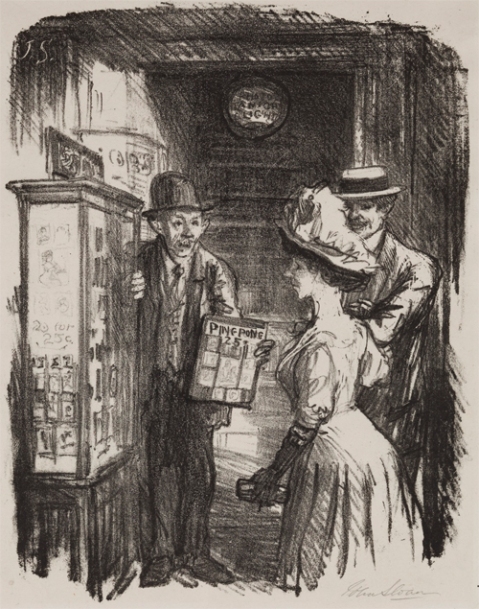

The Kansas City Star‘s verbal portrait of the ping pong artist is nicely complemented by a John French Sloan print called “Ping Pong Photos” (1908), which shows a photographer in the act of making his sales pitch. This work was reproduced at reduced scale in Harper’s Weekly 62 (March 4, 1916), p. 226, to illustrate “an exhibition of modern art unique in the wide scope of its appeal,” but a good scan of one of Sloan’s original lithographic prints is also available online courtesy of the Detroit Institute of Arts. By 1955, the “ping pong” photo had already been so thoroughly forgotten that Merrill Clement Rueppel described this same print in The Graphic Art of Arthur Bowen Davies and John Sloan as “showing a young couple considering the purchase of a copy of the magazine ‘Ping-Pong’ as held out to them by a derby-hatted news vendor” (Vol. 2, p. 305). Rueppel had been born in 1925, the same year the Photomaton was invented, so he would have grown up just as the profession of the “ping pong artist” was dying out. But there’s no question about what the print actually depicts, and if we look closely at the photographer and his display case, we can see a lot of interesting—and presumably accurate—detail.

For an insider’s perspective on the mechanics and economics of “ping pong” work, we can turn to James Boniface Schriever, ed. Complete Self-Instructing Library of Practical Photography, Vol. IX: Commercial, Press, Scientific Photography (Scranton PA: American School of Art and Photography, 1909), pp. 397-404. Note in particular the distinction this source draws between “ping pongs” and “penny pictures.”

As a means of catching the dimes and quarters of the young element, school children and visitors at resorts, the ping pong and penny pictures were inaugurated, with the result that this class of picture has become very popular and the making of them a very profitable business. To meet the requirements different camera manufacturers are now making suitable instruments, at a nominal cost, by means of which pictures can be sold for a penny each and give the photographer a good profit.

The term “Penny” Pictures is somewhat misleading, for they are really penny pictures in name only as a single picture could not be made for one cent. They are made and sold only in quantities, at the rate of one cent each. Usually the photographer supplies fifteen pictures for fifteen cents, no orders being taken for less than fifteen pictures.

Ping Pong Pictures are smaller than the penny pictures, and are usually made in strips of a half dozen, delivered unmounted or what is known as a “slip mount”. The aim of the photographer should be to sell mounts to his patrons for these pictures, they oftentimes bringing more money and more profit than the pictures themselves.

General Principles.—Instead of making one exposure on a single plate for this type of picture, the apparatus is so constructed that a 5×7 plate can be placed in a vertical or horizontal position and either one, two, four, six, eight, twelve, fifteen, eighteen or twenty-four exposures made on the one plate. The object is to make a large number of exposures on one plate, and after it is developed to print as many full size sheets of paper as the proposition calls for. As an example: If you have fifteen different exposures on one plate, and if you are offering fifteen prints for fifteen cents, then fifteen prints are made from it. This completes fifteen orders of fifteen pictures each, for which you receive fifteen cents each, or $2.25 for fifteen prints from one 5×7 plate.

To make the “penny picture” business a success, various methods must be used to increase the receipts. The prints can be finished in a variety of styles, and different positions can be made; in fact there is almost an endless number of methods that may be adopted. For instance, if fifteen pictures are sold for fifteen cents, one position only is allowed to each subject. Where different positions are wanted, twenty-five cents is usually charged, and three exposures made of five different subjects, on one plate (fifteen exposures altogether), from which only five prints are to be made. These five prints, therefore, bring you $1.25. Figuring the cost of the plate at six cents, the five sheets of paper at ten cents, and the plain cards at three cents, the total cost has been but nineteen cents. Card mounts of a better quality are usually sold with the higher class of work, and in addition to paying for themselves result in a greater profit than is made when cheap cards are used. The mounts, therefore, should be given consideration.

The actual work and the methods employed in producing the so-called ping pong or penny pictures—making and developing of negatives and final finishing of prints—are practically the same as in any regular studio. Most of the ping pong studios, however, are not supplied with the regular skylight, but an ordinary room, containing one or two fairly good size windows, is selected, and the methods of the home portrait photographer are employed in making the lightings.

Equipment.—The necessary equipment consists of a multiplying camera, camera stand, a few plate holders and a few trays for developing the plates and finishing the prints.

As only bust or half-length figures are all the ping pong photographer attempts, only one or two small plain backgrounds is all that is necessary. Generally two are used, a light one and a dark one. Comical make-ups are a novel feature of ping pong pictures, so one’s list of accessories might be increased and a few costumes added, such as odd hats, a dilapidated silk hat, an old style derby, canes, false moustaches, or any other paraphernalia that might be used in a stage make-up.

The Camera.—There are on the market various types of cameras which may be procured at a very reasonable figure, any of which will answer the purpose. These cameras are specially arranged for the making of a number of small pictures on one plate. In Illustration No. 132 is shown the Seneca View camera, to which is fitted a Multiplying Back, which latter is shown more in detail in Illustration No. 133. This instrument, in addition to being available for penny or ping pong pictures, can also be used for cabinet size portrait work or postal cards, as well as for view work. The B. & J. Multiplying Attachment shown in Illustration No. 134 can be adjusted to any ordinary portrait camera. Both of these attachments are simply constructed, easily operated, and form good examples of the general type of outfits on the market.

Camera Stand.—While any regular portrait camera stand, or even the regulation tripod intended for view cameras, may be employed, yet when the stand is preferred, one light in weight, that can be “knocked down” should be selected, for then it may be boxed in a small space for shipment.

Lens.—Any lens may be used, but, naturally, one of short focus and good speed should be chosen. The manufacturers of cameras equip their outfits with or without lenses, and also supply the lenses separately, at a moderate cost.

Lighting the Subject.—Under the ordinary studio skylight the subjects usually are placed in open light. When the ordinary window is employed a room is generally selected with the window facing the north. The subject is placed within a few feet of the window and slightly back of it, so as to receive the full benefit of all the light entering. The usual background is placed back of the subject. When but one style of picture is made, all subjects are seated, and, generally, the chair is made stationary. This avoids the necessity of focusing on each subject, for when once in focus the camera will need no further adjusting, no matter how many different subjects are photographed.

Operating the Multiplying Attachment.—The manufacturers of cameras and multiplying attachments supply complete instruction for their use, which is so very simple that further mention here is unnecessary.

Developing and Finishing.—Tank development is usually employed for this class of work, complete instruction for which is given in Volume II of this library.

Printing.—Either glossy printing-out paper or glossy gaslight paper is used for penny and ping pong pictures. Complete instruction for their manipulation will be found in Volume IV.

Mounting Prints.—In order to obtain a high gloss the prints are squeegeed onto ferrotype plates. After rolling the sheet print and the ferrotype plate into contact, mopping off the surplus water, apply ordinary mucilage to the back of the prints and allow them to dry. Then they may be cut apart the backs moistened with a damp sponge, and, like an ordinary postage stamp, attached to the mount. If slip mounts are used it is not necessary to apply mucilage to the back of the print.

Ping pong pictures are generally made in strips of five exposures, and are delivered unmounted. When mounted usually the slip mounts are employed; they require no pasting.

General Notes.—The making of ping pong or penny pictures is entirely mechanical in every respect, and each exposure must be accounted for.

There must be no re-sittings, no proofs shown, and the pictures taken on one day should be ready for delivery the next.

Get all the extra money you can by selling mounts.

Keep on hand a variety of different styles and prices of mounts.

These pictures are seldom ever retouched. When it is requested an extra charge should be made for the retouching.

Advertising.—A very common method of advertising is to place on the front of the building a large canvas sign, reading: “Your photograph for one cent.” On all such orders you would make fifteen pictures, one position, mounted on cheap cards, for fifteen cents. In some localities you may see signs which read, “Your photograph for 5 cents,” or possibly 10 cents. In such cases they usually make a trifle larger picture, or, perhaps, more than one position, and make each order amount to fifty cents. If they should advertise five-cent pictures, they would supply ten prints for 50 cents, and in the case of ten-cent pictures, they would supply five for 50 cents, or twelve for $1.00. The prince of such photos will need be fixed according to circumstances and location.

As previously stated, the money in penny and ping pong pictures lies in the quantities ordered and in the selling of suitable mounts for the prints. Slip mounts are to be preferred, as they save the bother of pasting and mounting, for the prints and mounts are usually delivered in separate packages, leaving the slipping of the pictures into the mounts to the customers themselves. The slip mounts are very attractive little mats, many of them having embossed borders, with openings displaying one, two, three, four or five faces, either oval or square, and they are designed to take the place of “paste on” mounts. The print being inserted saves much time in mounting. Of course the regular mounts may be employed, but slip mounts give a finished appearance to the photographs far superior to the plain ones, on which the prints have to be pasted.

A novel method of advertising is to circulate small cards among school children, these cards to be neatly printed, bearing some inscription similar to the following: “I am going to have my pictures taken at the Gem Studio, to exchange with my schoolmates, 15 for 25 cents, five positions, and get those pretty cards to mount them on.” To make this card more attractive have a small half-tone of some cute picture printed on one corner of the card, and have your address in neat type at the bottom.

There’s no shortage of books and web presentations devoted to photobooth pictures, which have attracted lots of attention in recent years. However, I know of only one major digital resource available for “ping pongs”: the Duke University Libraries’ collection of hundreds of glass plate negatives taken by itinerant photographer Hugh Mangum. Many of Mangum’s plates contain “ping pong” sequences—for a few representative examples, see here, here, here, here, and here—and these furnish excellent material for understanding the genre, which I’m eager to mine further myself. Nothing else seems to exist out there on such an impressive scale, but the Illinois Digital Archives offers several examples of “ping pongs” held by the Towanda Area Historical Society, identified as “Photographs called ‘Penny Pictures’, ca 1906 – 1910.” Some bloggers also post “ping pongs” from time to time, including Katherine Anne Griffiths of Australia, who recognizes that they weren’t made in photobooths and so puts them on her Mugshots and Miscellaneous blog, categorized as “penny photos,” rather than on her main Photobooth Journal site. Another blogger, Caroline E. Ryan of Bowlers and High Collars, isn’t as sure of what she has and writes: “I’d like to find out why strips like this one existed before the era of the Photomaton, but info on photo strips taken prior to Josepho’s invention isn’t readily available online.” I hope the present essay will help fill that gap, at least until such time as I can pull together the hefty coffee-table book which I imagine would be needed to do real justice to the subject. Some other related topics I may cover here in the future are:

There’s no shortage of books and web presentations devoted to photobooth pictures, which have attracted lots of attention in recent years. However, I know of only one major digital resource available for “ping pongs”: the Duke University Libraries’ collection of hundreds of glass plate negatives taken by itinerant photographer Hugh Mangum. Many of Mangum’s plates contain “ping pong” sequences—for a few representative examples, see here, here, here, here, and here—and these furnish excellent material for understanding the genre, which I’m eager to mine further myself. Nothing else seems to exist out there on such an impressive scale, but the Illinois Digital Archives offers several examples of “ping pongs” held by the Towanda Area Historical Society, identified as “Photographs called ‘Penny Pictures’, ca 1906 – 1910.” Some bloggers also post “ping pongs” from time to time, including Katherine Anne Griffiths of Australia, who recognizes that they weren’t made in photobooths and so puts them on her Mugshots and Miscellaneous blog, categorized as “penny photos,” rather than on her main Photobooth Journal site. Another blogger, Caroline E. Ryan of Bowlers and High Collars, isn’t as sure of what she has and writes: “I’d like to find out why strips like this one existed before the era of the Photomaton, but info on photo strips taken prior to Josepho’s invention isn’t readily available online.” I hope the present essay will help fill that gap, at least until such time as I can pull together the hefty coffee-table book which I imagine would be needed to do real justice to the subject. Some other related topics I may cover here in the future are:

- The relationship between “ping pongs,” other kinds of photo matrix, and motion pictures with the potential for animation.

- The stylistic evolution of the “ping pong” from the 1890s through the 1920s.

- Common “ping pong” props and poses. I’m especially interested in subjects posing with telephones.

- “Ping pong” shots, strips, and montages that stand out as particularly unusual. What were the outer limits of the genre?

For now, though, I’ll close by quoting a few sympathetic words spoken by Thomas R. Halldorson on March 21, 1918, at the annual convention of the Photographers’ Association of the Middle Atlantic States (reproduced in the Bulletin of Photography, April 17, 1918, p. 366):

In Chicago I used to pass a little show case on the North Side that was very uninteresting to me, because of the small pictures, many of them being ping pong pictures. One day I stopped and took a look into those pictures, and what I saw I wish I could express to you and reproduce for you here. In those little ping pong pictures there was more than I have often seen in pictures that photographers get $65 a dozen for. In every one of those pictures I saw the personality of somebody. I saw in those pictures something that made me feel that photography was a fine thing.

This is so interesting. I have a number of these in my family’s collection and never knew that they were known as “ping pong” photos or how they were made. Great examples and quotes!

Love old photographs, love learning something new everyday; thanks! I had not heard of the term “ping pong” photos before, but do have some from my grandfather’s day. Very nicely done post.

Thank you for the post!

Congratulations on an interesting and well researched article. I have been trying to research formats of small early 20th century portraits produced by commercial photographers in the Uk and appreciate how difficult it is to piece this all together. In the Uk most of these tiny photos, often of working class people, don’t even have a name to describe the format. Neither “Ping Pong” or “Penny Portraits” appear to have been used here, nor are the UK images quite the same – but they are interesting to compare. What I have so far is at http://www.fadingimages.uk/subgenre.asp. Best wishes. Les Waters.

It was very interesting to learn the history of these photos. I have a number that have been passed down in my family.

The idea for the ping pong photo is attributed to M. W. Wade (Madison Wright Wade). He called it the “little photo” and came up with the idea in the 1890’s while under the employ of Chas. T. Pomeroy, a photographer in Kansas City, MO. If you would like more details about this, please let me know.

This is an extremely interesting discovery — many thanks for sharing it! Searching on “M. W. Wade” just now, I turned up an article, “Whence Come Small Photos?,” in the St. Louis and Canadian Photographer 26:2 (February 1902), 72-3: https://books.google.com/books?id=gLsaAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA72 — which verifies what you’re reporting here. Is that your source? I agree that the article clearly describes the ping pong photo (although I’d missed it because it doesn’t use any of the search terms I was relying on), and the date of origin (1897) rings true — the earliest dated example I’ve seen so far is still the “grid” from 1898 shown in my blog post. The information in the same article that Wade was born in Logan, Ohio, on June 1, 1866, would surely help pinpoint him in census records and the like. In any case, I believe you’ve filled in an important piece of the story, and of course I’d welcome any more details you might have about Wade and his work.

I had not seen the “Whence Come Small Photos?” article. That was extremely interesting and has helped me fill in some gaps about Wade, his past, and has confirmed his participation in this interesting form of photography. I got my information from this newspaper article from July 17th, 1901: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84028140/1901-07-17/ed-1/seq-8/

The article is in column three at the bottom titled: “Four Years Old Today – Wade’s Famous Little Photos.”

It states “Mr. Wade is not only the original starter and founder of the small photo business, but has undoubtedly attained more personal success and is giving more general satisfaction than any other person in this line of work.”

I didn’t make a connection between “Little Photos” and “Ping Pong Photos” until I found your article. That happened because of a book I was reading “Ohio Photographers 1839-1900” https://www.amazon.com/Photographers-1839-1900-Diane-Vanskiver-Gagel/dp/0806356693/ref=sr_1_15?keywords=book+ohio+photographers&qid=1552060731&s=gateway&sr=8-15

In that book it states that Wade came up with the idea of the Ping Pong photo. I had no idea what a ping pong photo was and thought perhaps it was a strange typo where they had meant to type “Penny Photo”. A search of Ping Pong photo led me to your site.

This entire research adventure has come about because I have a hundred or so of these Ping Pong photo strips from Wade’s studio and it got me very curious as to what they were. At first I thought they were just proof sheets they would show to clients to see what photo’s they wanted to have enlarged. But have since learned from you site and others what they really are.

Remarkable! I see that the Akron Daily Democrat article you found even gives the specific day Wade opened his business: July 17, 1897. Maybe we should start celebrating July 17th as Small Photo Day? And of course I’m excited to learn you have a collection of actual strips from Wade’s operation, since it might be able to provide some unique insight into how early “ping pong” sessions worked. I’m guessing Wade’s studio must be identified by a studio stamp on the back, or something similar? For the main Akron studio at 207 East Market, or one of the branch studios (and is every strip marked)? Wade seems to have stayed in the business for a good many years, so can you tell (maybe from clothing) whether your strips come from earlier or later in his career? It’s unusual for so many strips to turn up all in one place — do you have a sense for whether what you have is a hodge-podge of miscellaneous strips Wade or one of his employees might have kept (maybe prints which customers had failed to pick up), or a set of strips all taken of some particular group (sometimes later “ping pong” photographers took photos of all the students in a school, all the members of a club, etc.)? I’d also welcome any information you can provide about technical details (whether the strips are horizontal or vertical; how many images there are per strip; whether they’re square, circular, oval), and the specifics of what was being photographed and how (varying poses, or maybe even sequences of poses people were repeatedly coached through; serious or playful expressions; use of any studio props). Sorry to bombard you with so many questions — but what you’re describing really is an intriguing find!

Pingback: All Griffonage That On Earth Doth Dwell | Griffonage-Dot-Com

Hi Patrick, this is a excellent researched article on Ping Pong, something I was asked about by an American photohistorian friend 8 years ago and knew little about back then. I have been researching small format photos in Australia in particular, mostly gem tintypes, but also the paper formats. Richard’s website has also been incredibly revealing and helpful. Please feel free to get in touch. Cheers! Marcel, Brisbane, Australia.

Hi, Patrick. I can push your Nov/1903 reference ahead to the Jan/6/1903 Washington Evening Star, page 16, column 5. A short ad reads “Ping Pong Photos, 8 for 15c. 726 7th street n.w. bet. G & H Simpson1*”. Within a year of your find, and in the same city.

I hadn’t heard of ping pong photos before this evening. I came across a mention of them in a 1909 newspaper contest in which contestants were requested to send photos but that ping pong and tintypes would not be accepted. Googling to find more led me to your blog page.

Many thanks for sharing your find! It’s looking more and more as though Washington could have been the original home of the “ping pong” name for these photos.

Pingback: More on CC Lyon, the traveling photographer of the West Indies – cornerofgenealogy.com

I purchased several thousand glass negatives, photographs (of wich there were several hundred of the point ping photos), and letters that where found in the basement of a house in Youngstown, Ohio. Glass negatives are edwardian (c1910). The ping prong photos I’m guessing are late 10’s to early 20’s, but I still have not had a chance to really go through them and examine in detail. All the letters belonged to a photographer employed at Wade’s. Letters are dated from 1890-1950 so span a decent period of time. There was some Wade photo literature as well as a Christmas card from Wade to him. From that, I’ve concluded that this is an inventory of items that this employee kept. Why he did so, I have no idea. Perhaps these were photos he took while under Wade’s employ? Maybe they were going to get thrown out and he rescued them?